Photo via Case Western Reserve University

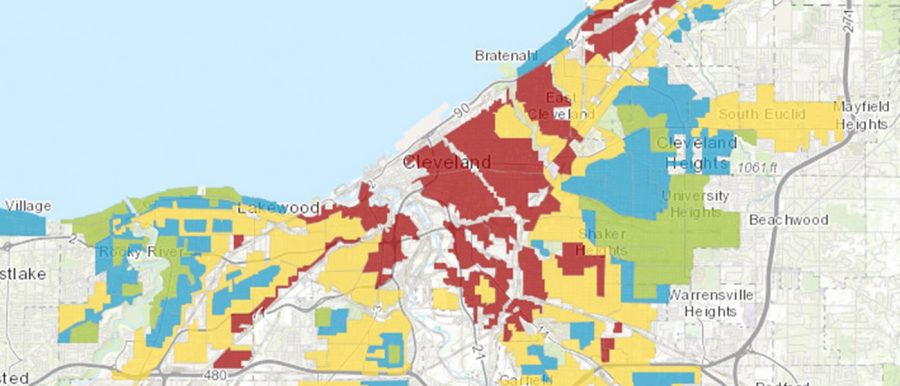

The red color indicates neighborhoods redlined in the 1930s.

Election feature: environmental racism in Cuyahoga County

This article is part of The Carroll News Elections Series, written by the students of the Fundamentals of Journalism class. For more information on these series, check out this introduction!

Imagine yourself in downtown Cleveland, driving though the busy streets. You drive by the Cleveland Clinic and see the new Sheila and Eric Samson Pavilion. Then you drive through Cleveland State’s expansive campus. You drive past Playhouse Square and underneath the world’s largest outdoor chandelier at the intersection of Euclid Avenue and East 14th Street, the sparkling crystals are connected by three golden arches.

Now imagine driving out of downtown Cleveland, getting onto Ontario Street, which connects to Woodland Avenue. As you drive, the buildings become shorter, construction is happening, shabby apartments line the street. Vacant buildings dot the land. You might think this is typical of places in and around the city and, unfortunately, it is in a place like Cleveland. These are the results of something called “environmental racism.”

For the purpose of focusing this broad term, environmental racism is the unfair treatment of communities of color regarding their living space. It has a deep-rooted history in Cleveland that began long ago and can be seen still today. Both the federal and local governments have taken steps to combat the issues that come with environmental racism. As with any large-scale issue, there have been successes as well as failures.

Some History

“It’s really a historic conversation” says Aaryn Green, Ph.D, diversity fellow at John Carroll University. “A lot of the reasons why those things [pollution, health problems] end up in minority communities are due to the fact that more privileged and more white communities have the power to resist,” she explained in an interview with journalism students at JCU on Oct. 14.

According to an article from Case Western Reserve University and The Journalist’s Resource, the practice of redlining began in the 1930s, which is why communities in Cleveland’s urban core are in an unequal state. Redlining is now an outlawed practice that targeted “problem” neighborhoods. The government’s mortgage lenders would outline neighborhoods that were a risky investment for mortgage seekers. These were usually communities with a large African American population or areas near these populations. Many who wanted to buy homes in redlined neighborhoods were refused home loans, as banks were wary of their ability to pay back the loans. This also inhibited homeowners from selling.

“[Redlining] triggered and solidified racial segregation and that further resulted in disinvestment in those communities. Our populations of color were really not able to build wealth because they were limited in their access to wealth-building opportunities such as home ownership,” said

Martha Halko, interim co-director of prevention and wellness at the Cuyahoga County Board of Health and past coordinator for the Health Improvement Partnership-Cuyahoga. She has also been a principal investigator for the Racial and Ethnics Approaches to Community Health program since 2014.

Many of the neighborhoods that underwent redlining from the 1930s until 1968, when it was finally outlawed, are still feeling the effects today.

Impacts today

The forms environmental racism takes on are numerous. Physical living conditions like the quality of people’s air and water have the potential to be overlooked in communities of color. Naudia Loftis, a 2020 graduate of JCU and advocate for racial justice who works with the Tamir Rice Foundation, commented on the water quality in her neighborhood of Kinsman.

“I don’t drink the water at the house that I live in now. Not out of the tap, no.”

Even meeting basic health needs like exercise may be a challenge. Green recalled her experience of growing up in East Cleveland, one of the lowest-income communities in the entire U.S.“I think of my mother who still lives there, who uses a cane to walk around. She can’t easily go outside and take a walk, just to get her mind off things or to go out for recreation because the road is uneven.”

Resources like fresh fruit and vegetables can be hard to come by. According to a map of counties with food insecurities on the Feeding America website, about 15.9% of Cuyahoga County is “food insecure.” This is roughly 200,000 people.

Food deserts are a major contributor to this problem. Food Deserts are areas that lack access to food outlets like grocery stores. Residents in some neighborhoods may have to travel miles to find fruits or vegetables, yet many do not have cars. In addition, residents may only be able to afford food that is pre-packaged and less healthy. Processed foods could cause future medical problems, such as obesity and diabetes, according to multiple articles on Cleveland.com.

The current COVID-19 pandemic is also taking a disproportionate toll on communities of color, especially the Black community. “In the Cuyahoga County Board of Health’s jurisdiction, Black residents are more than two times as likely to test positive for COVID-19 compared to white residents, and Black residents are 3.5 times more likely to be hospitalized as compared to whites,” Halko explained.

In addition, minority communities may be more susceptible to spreading the virus. Green explains that many people in minority neighborhoods may only have one grocery store to gather at. Public transit may also be their only source of transportation. The people in these neighborhoods tend to have closer living quarters. Many may also be trying to support their families by working and accidentally bring the virus back home.

“People with significant resources can just move away from potential environmental problems,” says District 10 County Councilwoman Cheryl Stephens.

With more money comes more power. Even if something happens, like construction of a landfill, privileged communities have the resources to move.

Loftis explained that she loves her community of Kinsman. Many want improvements to their neighborhoods and don’t want to be forced to leave, she pointed out.

What is being done?

Environmental racism is something that is deeply rooted into our society. Many changes will need to be made to fix it, which can only be achieved slowly. Rising public awareness on these issues can help speed up these changes, for example, Cuyahoga County declared racism a public health crisis this past summer.

Halko believes the Cuyahoga County Board of Health has done a good job of raising awareness and understanding among community members and partners on how structural racism impacts health. She does think there should be a broader policy change though.

However, the administration of President Donald Trump has not put much focus on environmental equality, “Our current president has decided that environmental issues are not a problem,” said Stephens bluntly. “Our government is not being aggressive enough when dealing with racial and environmental equality.”

The upcoming election may invite needed change, Stephens said. “I am confident that a Biden-Harris ticket can tackle the issues involving the environment and race.”

One issue Stephens said she believes Former Vice President Joe Biden will address is the problem with affordable housing. As stated before, many people in minority communities have a hard time in the housing market due to environmental conditions. Stephens thinks Biden will work for more affordable housing for all communities.

Current Congresswoman Marcia Fudge and her opponent Laverne Gore were both contacted several times to comment on these issues. Both women are running to represent Ohio’s District 11, which includes University Heights, in the federal House of Representatives. Neither has responded.

Future solutions

Without a doubt, voting is one of the most important things individuals can do. We have the power to choose the lawmakers that make the policy changes needed to help resolve environmental racism.

Stephens stressed the importance of young people getting involved in other efforts besides voting. She explained that even taking small steps, like not littering, is a great start.

Education is also a large part of understanding these problems. Whether that be educating yourself or others, this is an important step in order to make progress in the future. “You need to understand the root causes and then look for opportunities to engage,” urged Halko.

“Be willing to have the conversation,” Green said. She explained that by educating ourselves we don’t need to leave things to the “higher-ups.”