The word stoic is thrown around far too loosely today, and some who use it do not firmly grasp the proper meaning of the term. Most use ‘stoic’ to describe one who is numb, not feeling or showing emotion. It follows from this misunderstanding that a stoic ought not to cry. Moreover, crying, especially in men, is perceived as a sign of weakness and lack of emotional stamina. Women cry an average of 30 to 64 times per year; for men, it’s only an average of five to 17 times per year.

When we say ‘stoic’ we are referencing an ancient Greek and Roman school of philosophy; whose founders, thinkers and practitioners most definitely cried. We should be cautious to throw this label around aimlessly. Stoic philosophy does not proscribe a numbness or utterly emotionless existence— that would contradict our human nature for it is human to have emotions. Rather, stoics strive to live in accordance with our nature. For clarification on how one can live in accordance with nature, look to the writings of Chrysippus:

“[L]iving virtuously is equivalent to living in accordance with experience of the actual course of nature. . . . for our individual natures are parts of the nature of the whole universe. [A] life in which we refrain from every action forbidden by the law common to all things, that is to say, the right reason which pervades all things. . . . And this very thing constitutes the virtue of the happy man and the smooth current of life…” (7.87-88)

Real stoics cry: it’s human. Crying (I am only referring to emotional tears) serves a purpose at the right time and in the right place. In the right context, it can reduce stress, enhance relationships and reduce pain. It would be egotistical to say that you will not cry for it is simply part of being human—it is, in fact, uniquely human! Does this person mean they are above humanity? Or not human? If it is within human nature to cry, and the stoics demand that we live in accordance with our nature, and crying is part of our nature, then we should cry.

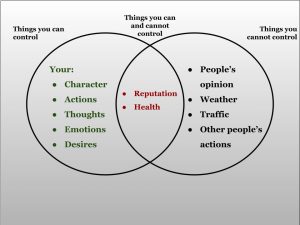

To me, stoicism boils down to two words: control and indifference.

The stoics believe that we should only direct our attention and energy to that which we can control. If you cannot influence it, worrying about it does no good. However, control is different for all of us. To Marcus Aurelius, a Roman Emperor who reigned from 161 to 180 AD, control meant not abusing his power and influence.

In “Meditations,” Aurelius advises us that we can live a good life “[i]f we can learn to be indifferent to what makes no difference.”

Epictetus, a Greek Stoic philosopher who lived during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, had to accept that he could not control his body as he was a slave. However, he realized he could control his thoughts, and, thus, he had freedom. He said,

“Curb your desire—don’t set your heart on so many things and you will get what you need.”

Stoicism is about controlling your emotions instead of letting them control you. Reason, not whimsical emotional woes, ought to guide your actions. When something is out of your control, and does not affect you, be indifferent! If your opinion or emotions will not change anything or bring you what you desire, why express them?

To that, I say, sometimes we need to feel. Thus, I stray from a strict reading of stoicism. Even though you may not control an event, strong emotions, and even tears, may be warranted. Cry because you want to cry. Not because you cannot control your emotions.

We must truly look inside ourselves and confront our emotions. Running from your thoughts and feelings under the guise of a ‘stoic’ dogma is a fool’s errand. The stoics teach emotional intelligence and detachment, not the elimination of emotion.

There was recently a loss in my family. A narrow reading of stoicism says that I cannot control this, thus I should be indifferent, etc, etc. That’s a load of crap, frankly. Moreover, it is an ignorant reduction of the core tenets of stoicism. I can be sad and cry. That’s an acceptable and normal reaction; however, I must be cautious of how long I sit in these feelings to avoid being consumed by them.

On crying, can you control whether or not you cry? Yes, but there is a right time and a right place. The four stoic virtues— temperance, courage, justice and wisdom— help us answer the question of when tears are justified.

Be disciplined (temperance), and determine whether you need to cry. Ask yourself, is this necessary? Save your tears for the right thing. Be courageous, and disregard what society tells you is appropriate about crying (this is especially important for men). Be just and determine what is right and fair, especially when the going gets tough. Don’t cry for attention. Lastly, be wise. Strive to be able to distinguish the differences between the good, the bad and that which you should be indifferent to.

To read more of my columns on stoicism, click here.

Listen to my podcast episode about stoicism!