On Feb. 22 John Carroll University’s chapter of the Ohio Innocence Project-U (OIP-U) brought students together to learn about the events that preceded the wrongful conviction of Laurese Glover, Eugene Johnson and Derrick Wheatt; also known as the “East Cleveland Three.” The student-run organization took the learning a step further by adding the insights of Dr. Dan Winterich and Dr. Melissa Berry to elaborate on the miscarriage of justice that sent Glover and his friends to prison for 20 years.

The Innocence Project estimates that one percent of the US prison population, just about 20,000 people, is falsely convicted and serving prison sentences. Wrongful convictions are even more concerning as 196 former death-row prisoners have been exonerated since 1973. The National Registry of Exonerations claims that there have been 3,478 exonerations across the country since 1989 which equates to more than 31,000 years lost. In Ohio alone, 59 people have been exonerated for crimes they did not commit.

JCU OIP-U’s event, “Anatomy of a Wrongful Conviction,” used the story of “The East Cleveland Three” to demonstrate how wrongful convictions can occur while also revealing the damage to individuals that comes from being imprisoned for a crime one did not commit. The pain and trauma Glover endured would likely stay with him for the rest of his life. Even after being out of prison for nine years, he said, “I’m still transitioning out…I’m in counseling right now.”

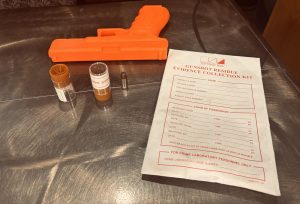

The talk started with a brief lecture from Winterich, who spent over 20 years working in law enforcement, including the Ohio Attorney General’s Office in the Bureau of Criminal Investigation, before transitioning to teaching at JCU and Lakeland Community College. Investigators used gunshot residue found on Johnson, Wheatt and Glover to charge them for the murder of Clifton Hudson who was only 19 when he was shot and killed. Yet, the field tests for gunshot residue only led to vague conclusions.

Winterich said, “So if there’s three people, right, one of them fired a gun, all three people could be positive for gunshot residue. How does that help me determine the shooter? It doesn’t.” He said “we just don’t use it like we used to in the old days.”

Then, Berry, an attorney and former fellow with OIP at the University of Cincinnati College of Law, explained how East Cleveland Police used faulty suspect photo line-up methods to charge the men.

Tamika Harris, 14, saw Glover’s truck, which he had just gotten the day before, fleeing the scene of the shooting. She initially told police she could not identify the shooter because she didn’t see his face.

But the truck led police to Glover, Johnson and Wheatt. Police brought the teen in three times, each time only showing photos of three men. The teen cracked under the pressure of police investigators and identified Johnson as the shooter. Police then used traces of gunshot residue found on the men to charge them. Harris later recanted her testimony which helped exonerate the men.

On Jan. 17, 1996, Wheatt and Johnson were convicted of murder and using a firearm. They were each sentenced to 18 years to life in prison. Glover was convicted of murder and sentenced to 15 years to life in prison; Glover was only 17 years old.

Glover recalled, “When the judge sentenced us, he told us that if he could give us more time, he would. So on every [Feb.] 10, he ordered us to go to solitary confinement.” After three years in prison, he managed to avoid solitary confinement (known to incarcerated individuals as “the hole”) until one morning guards woke him up and told him he was going to the hole.

Glover remembers the guard saying, “You know today’s date? He’s like, ‘look,’ it was February 10. I couldn’t believe it…we went to solitary confinement for one day to think about what we did.”

“Look, if it was like one of the worst places ever…I mean, prison is never a great place to start off. It was a lot of gang fights and different things like that,” Glover said about his 20 years in prison, “But the only thing that made it not as bad was that when they put us out in the hole, it was all next door to each other. And we’re all in the same prison…I think it would have been even worse if we didn’t have each other to lean on.”

Now, Glover is experiencing the frustration that many exonerees and the formerly incarcerated go through to find jobs. He said, “A lot of places didn’t want to hire me because I had this huge gap of not having employment. So I got to explain why I haven’t been working.”

When asked if prison helped rehabilitate him or reintegrate him back into society, he said, “I don’t think they offer enough for people after you go through that experience to come out to live a better life. Like we need to have [prisons for some] guys…but they also should have better programming, better vocational [training], so people…won’t go back to the streets and commit crimes.”

Glover stated, “I definitely think it’s broken,” when asked about the functionality of the criminal justice system.