Power and Bread

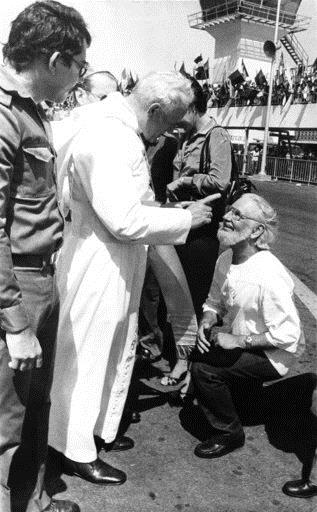

St. John Paul chastises Jesuit priest Ernesto Cardenal, a cabinet official of the Sandinista government. Photo from AP.

Dec 6, 2018

In a recent meeting with The Carroll News’ editorial staff, a JCU administrator characterized the end-goal of the Christian mission as “the liberation of people.” While (if you take quite a bit to be implied — essentially, that by liberation we mean the liberation of souls from sin) this could be technically correct, the wording is deliberately vague, and its historical employment, especially connected to the Jesuits, has been both heretical and dangerous.

The use of the word liberation in this context cannot be detached from the school of theology which it describes. And liberation theology, regardless of the efforts of American Jesuit academics to sanitize it, is Marxist political thought transplanted into a Christian theological context. If the movement’s central texts are not evidence enough of this fact, we can look to the testimony of Ion Mihai Pacepa, a three-star Soviet general and foreign intelligence operative who defected to the United States in 1978. In a 2015 interview with the Catholic News Agency, Pacepa revealed that the KGB had been the driving force behind the rise of this new theology in mid-century Latin America. It had been, essentially, an attempt to make Soviet political doctrine more palatable to a deeply Catholic continent.

After years of formation in theological-academic writing and important conferences of Latin American Church leaders, liberation theology found its only practical implementation in Nicaragua in 1978. A violent revolution, among whose leaders were a few prominent Catholic priests — most of them Jesuits — overthrew the country’s dictator and replaced him with another one — this time a Marxist, Daniel Ortega. Five of those revolutionary priests secured cabinet positions in Ortega’s Sandinista junta. The bloodshed and oppression of post-revolutionary Nicaragua are well-known and need not be recounted here. What we often forget, however, and what is worth remembering, is that members — leaders, even — of the Catholic Church engaged in this violence at the highest levels, all in the name of liberation. They paid no attention to the repeated and fervent exhortations of St. John Paul to put an end to their horrific actions.

Perhaps the only tenet of liberation theology that can be addressed on purely theological grounds — for there is very little theological in the whole of its literature and thought — is its concept of collective social sin. This deep misunderstanding of the natures of sin, the soul and society was unequivocally condemned by the Church, and it was one of many reasons for official notifications and censures that the Vatican has been forced to issue against the movement’s leaders. The Catechism reminds us that sin, properly understood, can only be discussed as a personal act; it is the failure of the individual soul to obey the eternal law.

“Social sin” can be a productive concept, but only when recognized as “the expression and effect of personal sins.” In the Christian worldview, the responsibility for actions lies with people, because we are intelligent beings with moral autonomy. In the Marxist worldview, the individual is submitted to the abstract forces of History, which charge on relentlessly and trample over powerless people, and must be disrupted — must be overthrown.

This Marxist worldview is, importantly, materialistic. The story of man is taken as the story of physical beings in a physical world. The things which are most important for man’s fulfillment, then, are material and temporal: a man needs food to nourish his body, and a man needs money to pay for the food. When you convince that man that some impersonal, macroeconomic bogeyman is set up to keep him from the money that will liberate him, and that class warfare or the radical disruption of social order are the only ways to defeat that bogeyman, he becomes willing to fight. When you sell him on the great blasphemy of liberation theology — that Christ mandates this political revolution, that it is, in fact, the center of the gospel message — you convince him that he has a moral obligation to engage in conflict against his fellow man.

Of course, its proponents never present the path to liberation in these terms. It is presented as a humanitarian necessity to reform temporal governments in the Marxist model (though it is rare even for the liberation theologians to employ this word openly). Governments, the wealthy, even the Church itself, are presented as enemies of the poor, whose ultimate goal is liberation in opposition to these oppressors.

Nothing is said of salvation. and little is said of the soul, the bulk of whose existence has nothing to do with economics. Who we are and what we ought to do is mandated by the pursuit of political and economic equality, by our place and participation in the long march of History.

In his landmark Jesus of Nazareth, Pope Benedict XVI recognizes the insidious falsehood of the liberation heresy: “Moral posturing is part and parcel of temptation. It does not invite us directly to do evil — no, that would be far too blatant. It pretends to show us a better way, where we finally abandon our illusions and throw ourselves into the work of actually making the world a better place. It claims, moreover, to speak for true realism: What’s real is what is right there in front of us — power and bread.”