The effect of systemic racism at JCU and across the nation

Nov 25, 2020

Naudia Loftis, ’20, was faced with a decision while she sat in class at John Carroll. Was it her job to be the voice for her inner-city, primarily African American community or to stay silent?

In her Arrupe classes, Loftis told a journalism class this fall, she often felt called upon to represent the minority voice. Yet it was not her job to do so. She would teach the others in the class what it was like to be a member of a visible minority. But like the other students, she was there to learn, not to teach.

In one Theology and Religious Studies class, her professor made racially offensive comments, and Loftis thought it would be best to be silent. Loftis said she kept it together while hurtful comments were made about her community. When asked by another student about how she coped with the insulting language, Loftis knew she had the right to do something, so she reported the professor for his comments.

Loftis has quite a different background from many John Carroll students. She grew up in Kinsman, an inner-city Cleveland community that is often overlooked by the government and media. Loftis had a tough transition to John Carroll, though she said she would not have changed it. Among other things, John Carroll provided her the opportunity to meet and work with the mother of Tamir Rice, a Cleveland child shot by police at age 12 while playing with a toy gun. Propelled by her own experiences of losing family members to gun violence, Loftis now works very closely with Samaria Rice, Tamir’s mother, as an activist with the Tamir Rice Foundation.

Choosing when to speak up or be politely silent is not only a problem for minorities at John Carroll. Minority group members experience these problems at schools, businesses and organizations everyday. Race problems happen every day, though they present themselves in different magnitudes.

During an interview with the Latin American Student Association, a member shared a story about racial profiling. After the United States Hispanic Leadership Institute conference in Chicago in the fall of 2018, LASA members took the train back to John Carroll. They traveled home filled with positive energy from the conference. During the trip home, the train was stopped by the Border Patrol, a story covered by The Carroll News at the time.

While most people on the train did not turn their heads, the members of the Latinx community were forced to scramble for their IDs. These John Carroll students should have felt no pressure to find their IDs as they were all American. Still, they did. Border Patrol did not have a legitimate reason to question why they were there. The LASA members felt drained from this unpleasant interaction. They rode in silence the rest of the way back to Cleveland.

Following their return to campus, a few LASA members felt a need to talk to someone they trusted. “Student orgs are meant to be a safe place on campus, especially when there’s a lack of support and representation within our own community,” said Josie Sobek ‘21, a LASA member. The incident with the Border Patrol made a safe place feel not so safe.

Many in LASA turned to the organization’s former advisor, one of the few staff members at John Carroll that belonged to the Latinx community, and other trusted faculty members who listened to the students’ concerns. The students brought attention to the fact that there is little diversity in faculty members at John Carroll. The LASA members felt that while others could hear their story, they would never truly understand how it felt to be on the train.

Racial profiling is something that happens all over America. While the interactions may only last for a few moments, it can stick with victims much longer. Having a support group that shares the same background can be critical to recovery.

Racial inequality also happens on a wider scale in America. In 2019, there were 940 hate groups in America, 31 of them in Ohio, and eight within an hour’s drive of John Carroll, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

In Akron, Ohio, a mere 40 minutes away from John Carroll, there is a chapter of the Proud Boys. Designated as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, their founder Gavin McInnes describes the group as a “pro-western fraternity,” a drinking club dedicated to male bonding, socializing and celebrating western culture. But the group is described by SPLC as violent, nationalistic, Islamophobic, transphobic and misogynistic.

The Proud Boys were a point of discussion during the Sept. 29 presidential debate, when President Donald Trump was unable to condemn white supremacists and militia groups. Americans sat at the edge of their couches, as debate moderator Chris Wallace asked, “You have repeatedly criticized the vice president for not specifically calling out Antifa and other left-wing extremist groups. But are you willing tonight to condemn white supremacists and militia groups and to say that they need to stand down and not add to the violence in a number of these cities as we saw in Kenosha and as we’ve seen in Portland?”

After being unsure of what to say for a minute, Trump called upon the group: “Proud Boys, stand back and stand by. But I’ll tell you what somebody’s got to do something about Antifa and the left because this is not a right-wing problem, this is a left-wing [problem].”

For many Americans, who spoke out on traditional and social media, this response was not enough. The feeling that Trump did not clearly denounce the Proud Boys was felt across the world. This became one of the main takeaways from the first debate.

Racism in America appears in many forms. It’s a deep-rooted problem that has hope of being addressed with government officials who are ready to acknowledge the issues in America.

Following the rally organized by a white nationalist in Charlottesville in 2017, Trump condemned the events of the rally by saying: ”We condemn in the strongest possible terms this egregious display of hatred, bigotry and violence. It has no place in America.” However, this statement was made only after Trump received a lot of pressure for saying, initially, that there were “very fine people on both sides” a few days earlier. When Trump condemns a hate group, he is often responding to backlash for not doing so, which can be seen with both the Charlottesville rally and presidential debate.

Vice President-elect Kamala Harris wants Americans to acknowledge and address the deep-rooted race issues in America. On June 4, during a wave of protests following the killing of George Floyd, Harris spoke on this issue:

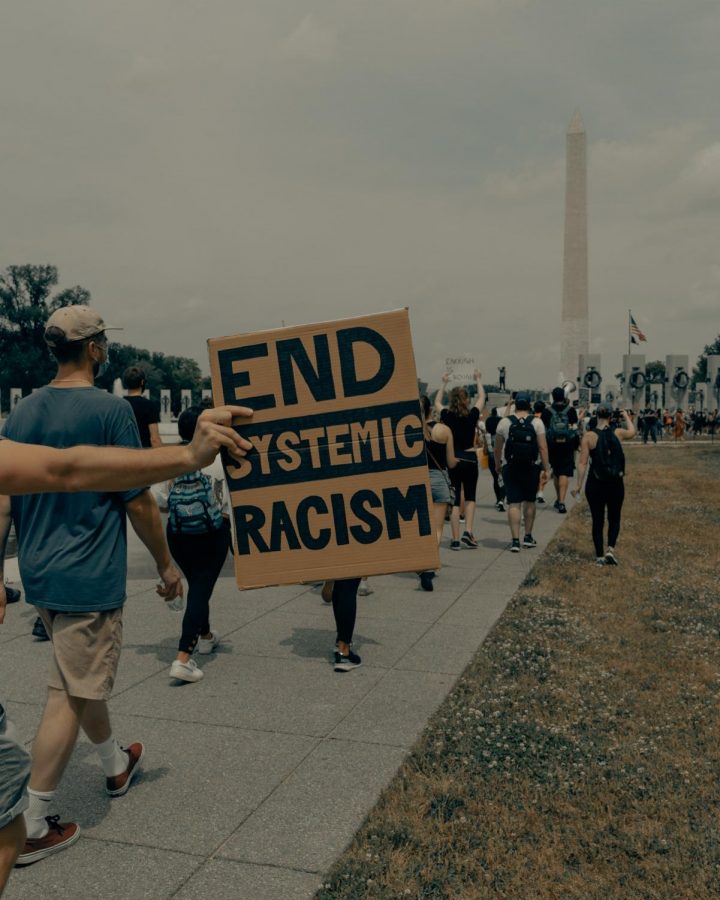

“Let’s speak the truth: People are protesting because Black people have been treated as less than human in America. Because our country has never fully addressed the systemic racism that has plagued our country since its earliest days. It is the duty of every American to fix. No longer can some wait on the sidelines, hoping for incremental change. In times like this, silence is complicity.”