Giba’s Claim: Sixto Rodriguez is superior to Bob Dylan

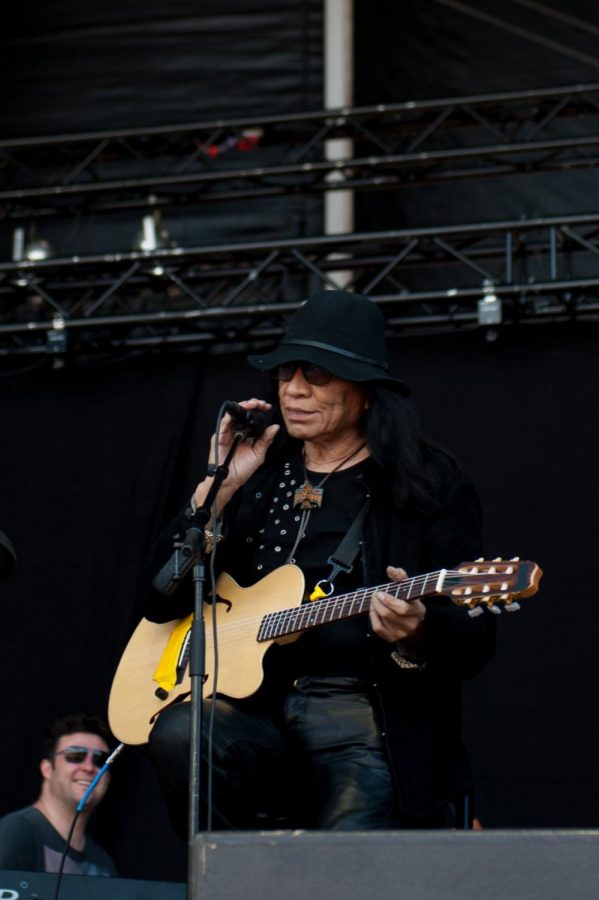

Rodriguez at Way Out West in Gothenburg, Sweden Aug. 9, 2013. (Kim Metso, Wikimedia Commons)

Sep 16, 2021

I’m sure you know the name Bob Dylan. But maybe this is the first time you’re hearing of the legendary Sixto Rodriguez, whose music, I’d say, is superior to Dylan’s. Rodriguez is the true embodiment of the working American spirit that Dylan’s songs are all about.

Singer-songwriter Bob Dylan is undoubtedly a staple of American pop culture. Born in Minnesota in 1941, Dylan went on to be one of the best-selling musicians of all time. Through intricate anthems that explored the social and political climate of the United States, Dylan’s songs like “The Times They Are A-Changin’” and “Blowin’ in the Wind” became canticles for civil rights and anti-war movements. Such songs solidified him as not only a symbol of the counterculture but also as an idol in the chronicles of American music, netting him awards like a Nobel Prize in Literature and a Presidential Medal of Freedom in the process.

Sixto Rodriguez — professionally known as Rodriguez — was born in 1942, roughly a year after Dylan, to a Mexican father and a Native American mother. As one of six born into an immigrant Mexican family who migrated to Detroit for industrial work in the inner city, Rodriguez came of age in the sixties and wrote songs layered with political commentary that illustrated the blight of struggles and hardships faced by the inner-city poor.

When comparing their music, it’s clear that these two midwesterners felt similar pangs of disillusionment toward the political and global unrest of the sixties and seventies, with events like the détente of the Cold War, Vietnam, the Civil Rights movement, and numerous national and worldwide political crises permeating their time. As the great writers of generations do, Rodriguez and Dylan channeled their frustration and musings with the state of the world into their music.

But while Dylan saw incredible success and critical reception of his music across the world, Rodriguez was practically a ghost in the United States. His first album “Cold Fact” was released in 1970 through Sussex Records as part of a two-record deal. He released his second studio album “Coming From Reality” in 1971. Both albums were considered flops, and few records were sold. He was soon dropped from Sussex, which itself closed in 1975, and not long after quit his music career in 1976. The whole time, he was working various industrial jobs ranging from house construction to restoration and demolition. His dream of musical success had seemingly departed, and soon after he bought a downtrodden dwelling from a federal government land auction for $50 ($225 in 2019), a house in which he still lived in as of 2013.

He then moved on with his life. He attended Wayne State University where he completed a bachelor’s of philosophy in 1981. He married and raised a family of three daughters. Rodriguez even pursued politics, a man ever committed to improving the lives of Detroit’s working class. In 1981 and 1993, he ran for Mayor of Detroit; in 1989, he ran for the Detroit City Council; in 2000, he ran for the Michigan House of Representatives. All attempts were unsuccessful.

However, Rodriguez did have success with his music in other countries. When his records sold out in Australia, a record label called Blue Goose Music bought the Australian rights to his recordings. They released his two albums as well as a compilation album called “At His Best,” which included unreleased singles. Australian concert promoters tracked Rodriguez down eight years later and brought him on a 15-day tour to tour Australia in 1979 and 1981.

Unbeknownst to Rodriguez, “At His Best” went platinum in South Africa during the mid-70s. His music soon spread throughout the country, and Rodriguez became South Africa’s own Bob Dylan as his songs became political symbols and cries of anti-apartheid sentiment. Rodriguez would eventually go on to sell more records than The Beatles and Elvis Presley. As his record label closed and his connections to the industry ceased, there was a missing link causing Rodriguez to not be cued in on his success. Rodriguez himself, known to lead a very simple life, possessed neither a telephone nor a cellphone of his own, so it’s easy to understand why he had no idea he had become a superstar on the other side of the world.

While South Africans loved Rodriguez’s music, he had never visited the country, and nobody had any indication of who he was –– let alone if he was still alive. Various legends had circulated throughout South Africa that attempted to explain the man’s mystery, with one popular theory being that Rodriguez had committed suicide by self-immolating on stage in the 70s shortly after the release of his second album. The apartheid government in South Africa had even begun censoring songs on his records, scratching off songs that were deemed a threat to the stability of the regime.

With South Africa’s transition out of apartheid in the early 90s along with the 1991 CD release of Rodriguez’s two albums by a South African record company, a few dedicated superfans decided it was time to solve the enigma of Rodriguez. The investigation marked the start for what would become the eventual 2012 Academy Award-winning documentary “Searching for Sugarman,” named eponymously after Rodriguez’s most successful song “Sugar Man.” South African Rodriguez aficionados began scouring his songs to look for any indication of what city he was writing about in the states, along with any identifying details such as names that would help with the search. Ultimately, though, the goal of the project was to figure out Rodriguez’s fate.

“No one knows exactly how the album came [to South Africa],” Malik Bendjelloul, director of “Searching for Sugarman,” told NPR’s Scott Simon. “But when it came, it just spread, and he became famous — and as dead — as Jimi Hendrix. Everyone knew his albums, and everyone knew that Rodriguez was completely dead.”

Years into the project, two journalists managed to get in touch with the producer of “Cold Fact.” They peppered him with questions, and he confirmed Rodriguez was still alive and kicking in Detroit as he had been for the past two decades. One of Rodriguez’s daughters also came across the website created by the South Africans dedicated to finding him. She reached out to the searchers, and the connection was established. His daughter got a phone to Rodriguez, and the two journalists called to confirm he was alive. He hung up the phone immediately.

“He thinks it’s a crank call, a practical joke,” Bendejelloul explained in the documentary. “So they call him again and say, ‘Listen, listen, this is true. Did you make an album called “Cold Fact”? … In South Africa, it’s more famous than “Abbey Road.”

What follows is the miraculous story of Rodriguez’s musical revival accompanied by a sold-out headline tour across South Africa along with more shows in Australia and New Zealand. Fans came out in droves to see Rodriguez, a singer seemingly returning from the dead.

Rodriguez returned briefly to the spotlight with newfound fame to his name (the Spanish origins of the name Rodriguez literally means “rich in fame” — ironic, I know) and started to find success commercially in the US, over fifty years after his musical debut.

So why was Dylan a success in America, and Rodriguez wasn’t — especially when their music was so similar?

I think in part, Rodriguez was not as marketable as Dylan. Like many minorities in the United States, Mexican immigrants in the 70s experienced alienation and marginalization. Rodriguez simply just didn’t have the same white face and name as Bob Dylan (who actually changed his name from Robert Allen Zimmerman in 1962).

Despite Detroit’s status as Motown USA, the record industry failed Rodriguez. Like many American authors who pass away fameless only to be discovered in subsequent generations, Rodriguez nearly slipped through the cracks. Fortunately, he’s still singing away, and we can appreciate the lens he gave us — just like Dylan.

To me, Rodriguez’s music is powerful, raw, desolate and bountiful all at the same time. The last song, “Cause” on his record “Coming From Reality,” opens with the following lines:

“Cause I lost my job / two weeks before Christmas. And I talked to Jesus at the sewer / and the Pope said it was none of his goddamn business.”

After he wrote these words, he ended up actually losing his job in music two weeks before Christmas.

Once I heard those words, I knew Rodriguez was special. Once I heard his story, I knew he was legendary. I hope you see that he is, too.

Celinka • Dec 28, 2024 at 6:39 am

I know one song of Rodriguez — I Think of You —and it was a hit here in the Philippines. But sorry, I believe Dylan is the better writer and lyricist. However this is not to undermine the talent of Rodriguez. He ‘s amazing. Plus he looks so Filipino

Ken Campbell • Sep 13, 2023 at 2:33 pm

I only learned about Rodriguez after he died. Watched the documentary and now listen to his music daily. He’s every bit the poet of Dylan – better, IMO. I find his voice soothing and haunting all at once but I love his songs.

To validate what we’ve all now heard about his fame in South Africa… I was having a beer at my local watering hole last night when a friend came in and said he was out on the patio entertaining a couple of friends from SOUTH AFRICA. So I had to ask…. Is Rodriguez REALLY that famous in your country?

His reply validated everything in your article. He said that the music of Rodriguez was the voice of multiple generations and everyone knows him. He was super excited to learn that I’ve come to love his music.

I know it is a couple of years old, but great writing here… thanks! Ken

Zlata Bell • Jan 8, 2024 at 7:00 pm

I was supposed to see him in concert in Australia, he cancelled, his arthritis was bad.

Then two years later passed on. I only really heard of him 10 years ago through my son that uncovered Sugar man documentary.

He will be sadly missed by a lot of people and artist. Bob Dylan is also in this league. ☮️

Dr. B • Sep 16, 2021 at 12:34 pm

Fascinating! I had never heard of Rodriguez until I read this. I will definitely check him out, as I used to be a big fan of Bob Dylan.

Barbara Barth • Dec 18, 2023 at 10:11 pm

Dylan predates Rodriguez! Rodriguez was a wonderful artist, but let’s stop giving him credit for influencing Dylan. The dates don’t add up.