Giba’s Claim: Oglethorpe’s “Georgian Experiment”

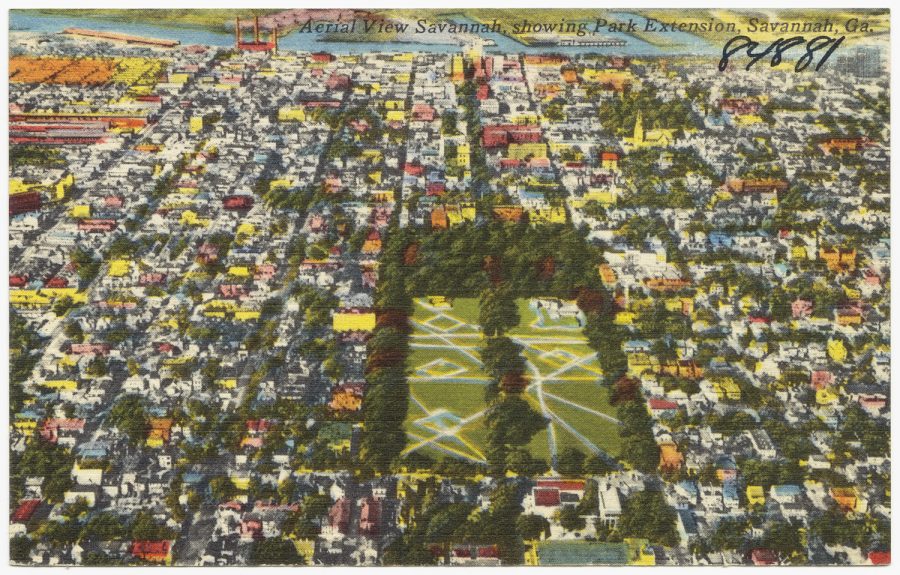

An aerial view of Savannah.

Over this past Thanksgiving Break I passed through Savannah, Georgia, for the first time on my way to Daufuskie Island to visit my girlfriend’s family. During my time in Savannah, my fascination was piqued by its rich and intriguing history — especially its young story as a colony and its renowned urban plan.

I met my Uber driver outside the airport and on the journey to Tybee Island (where I was staying for the night) we struck up a conversation. Quickly past the casual chit-chat, I was able to stay afloat in the conversation by riffing off whatever fragmented knowledge I had retained about the area from my AP U.S. History class in high school.

“Wasn’t Georgia founded as a buffer between the Carolinas and Spanish Florida?”

Somehow, I was hitting notes.

While taking me through the old city, my driver shared stories, and our discussion oscillated between different characteristics of the area’s history: Savannah’s notable Victorian and colonial architecture, its uncanny history of piracy, and status as the fourth-largest port in the United States, the city’s locale as the ultimate strategic destination of Civil War Union General Sherman’s March to the Sea.

Then, there’s the colony’s identity as “The Georgian Experiment,” where under its social reforming-founder, James Edward Oglethorpe, and alongside the other founding Trustees of Georgia, they had numerous interesting policies such as prohibiting slavery, the import of alcohol and lawyers from practicing.

What Oglethorpe and the Trustees envisioned was the creation of a classless society in Georgia.

In 1729, one of Oglethorpe’s friends died in a debtor’s prison from a cellmate’s smallpox as a result of his inability to pay for decent room and board in the prison.

In response, Oglethorpe led a campaign to reform England’s prisons. In the process, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, “Oglethorpe saw firsthand the horrible conditions, abuses, and extortion prisoners faced. He was also alarmed that so many British citizens faced jail for no other reason than indebtedness.”

During their investigation of the prisons, conversations between Oglethorpe and the Trustees proposed the idea that Georgia’s early colonists would be the “worthy poor”: debtors who “could be transformed into farmers, merchants, and artisans.” The motto of the Trustees seems on point to this effort, and oddly Jesuit: Non sibi sed aliis — “Not for self, but for others.”

In the years up to the journey to Georgia, this vision of the “worthy poor” failed in being utilized, but such social efforts in reformation were abundant in the spirit of the Georgian Experiment.

This rings true in that Oglethorpe and the founders deemed it essential that strict rules were needed to ensure the class divisions prominent in English society would not recreate themselves; all settlers then were designated to work and own their own lands, with slavery and large landholdings prohibited as to not imitate the wealthy plantation society in the Carolinas.

The egalitarian goal was not fully accomplished, however, as “women were not allowed to own land in the new colony. The Trustees based this policy on the assumption that each plot of land required a male worker (and armed defender).”

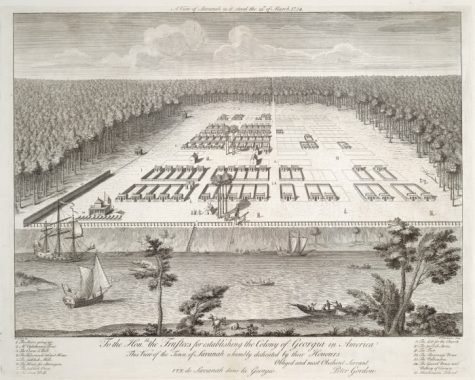

After more than five decades since England founded a new colony (a fascinating historical time gap), Oglethorpe and his expedition of 114 selected colonists eventually reached what is now Savannah in 1733. Oglethorpe and the Trustees had 21 years of charter before the territory was to be relinquished to become a royal colony.

Oglethorpe spent most of the next decade in Georgia overseeing its development economically, politically and militarily. Though he was not technically called Governor, he embodied the role and lived up to the Trustees motto. Though sometimes in violation of the Trustees’ regulations, Oglethorpe created a sort of religious haven of diversity in Georgia, where Jews, Lutheran Salzburgers and other persecuted religious minorities settled in safety. A stipulation, however, was Catholics were not allowed to settle until 1748.

He maintained his opposition to slavery and prioritized the colony’s relationships with the land’s Native Americans by respecting their customs, language and needs. Tomochici, chief of the Yamacraw Indians, was a close friend of Oglethorpe’s, and the two worked to establish peaceful relations between the colonists and the land’s indigenous people.

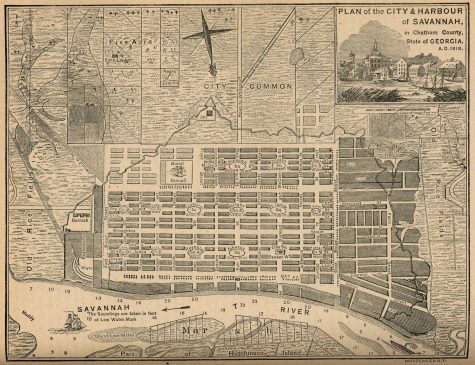

Full of notable achievements, one of Oglethorpe’s finest was the design and urban development of the city of Savannah itself. The design has come to be known as the “Oglethorpe Plan” and has been influential in the design of other cities in Georgia, South Carolina, and even recently in Quebec in 1993 where a 500-acre development in St. Laurent called Bois-Franc was built on an adaptation of Savannah’s street grid.

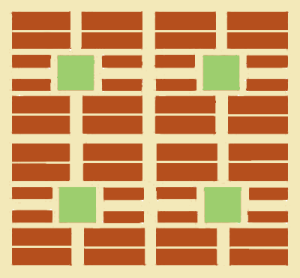

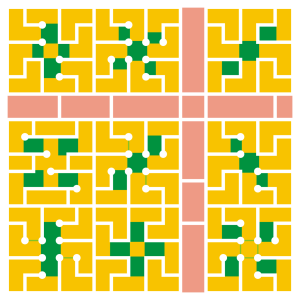

The city was laid out in wards, 600 by 540-foot blocks that organize streets and building lots around a central open space or square. The image below shows four wards for reference. From a glance, the environment is incredibly pedestrian-friendly and walkable with the connected and easily navigable neighborhoods oriented toward places for people to congregate.

Through such design, Oglethorpe laid out the foundations for an undivided community where the nonhierarchical location of the wards, squares, and equal-sized contributed to a dissolution of class divide, replacing it for an aspiring ideal egalitarianism.

As the city developed over the years, what’s resulted is “an urban forest of unsurpassed beauty and utility,” a visually stunning and architecturally diverse system of neighborhoods with numerous parks and gardens.

Today, 22 of the original 24 Savannah squares exist, and up until the 1850s, city planners laid out new squares of expansion according to Oglethorpe’s original plan. The plan achieved the elements of “organic” city growth, where one cell of wards contains a microcosm of an entire city.

The simplicity and brilliance of the design is palpable, and I wager that this design could influence the design of cities in the future — see below the contemporary Fused Grid network that seems to have drawn from the Oglethorpe Plan’s cellular nature.

Eventually after a series of conflicts with the Spanish, Oglethorpe succeeded in defending the colony in 1742; the Spanish would never again launch an offensive on the East Coast of America.

Oglethorpe would pursue the Spanish to St. Augustine, Florida, where their main fortress in the territory lay. However, the 1743 attempt was unsuccessful and soon enough he was called back to London. In the years following, he became involved in English affairs, defended the crown against a usurper, and was married in 1745.

He maintained his position on the Board of Trustees of Georgia, but despite his opposition, the Trustees “gradually relaxed their restrictions on land ownership, inheritance, rum and slavery. As a result, the general’s attendance on the board declined.”

By 1750, Oglethorpe ceased involvement with the Board. The remaining Trustees voted to return their charter to govern Georgia, which soon after became a royal colony in 1751. Thus ended the Georgian Experiment and the era of the Trustees. Soon after, the American Revolution took place, and Georgia would assimilate itself into the South and the colonial era in the new United States would come to a close.

I encourage you to visit Savannah and experience its rich history. It is a marvel, and it was my pleasure to experience its beauty and feel firsthand the legacy of Oglethorpe’s visionary urban design.