You should reread fairy tales

They’re way better than you remember

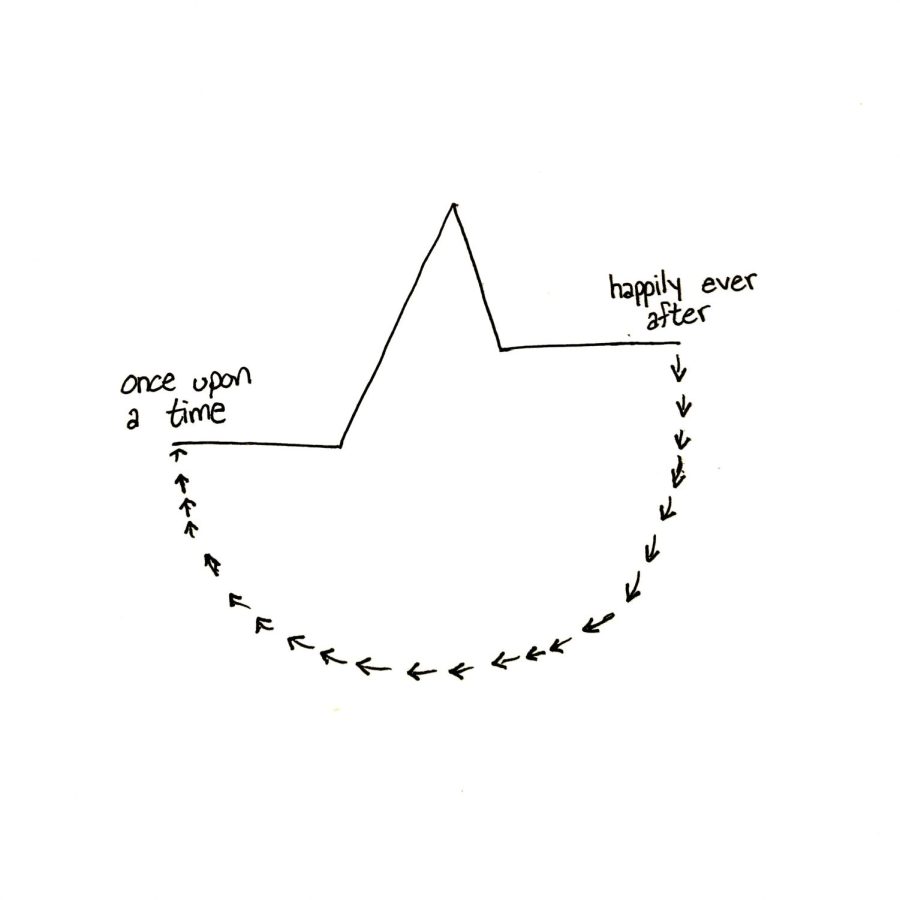

Accurate metatextual demonstration of fairy tale plot structure. Art by the author

Mar 1, 2023

Once upon a time, somewhere in between legend and lesson, between folklore and a dream, the fairy tale genre was born. Very far reaching, fairy tales include princesses, peas, three bears and porridge, beanstalks, red riding hoods, tortoises, hares, foxes and grapes, among many things likewise.

Though there are notable differences between fables and fairy tales, I use the terms interchangeably to include both, though most of my analysis applies better to fables.

When I think back to my elementary school days, I distinctly recall sitting in a semicircle in front of a teacher reading us such tales. I was spellbound by the storytelling process; I still am. There is immense value in fairy tales, though I had to dig through a pretty hostile view of them before I figured it out.

Fairy tales are not losing relevance, either. Though their target audience remains the young, fairy tales retain their bedtime-story charm. They’ve been revamped into Disney princess cartoons, adapted (often horribly) into movies, undoubtedly retaining a presence and significance. This column aims to put fairy tales under the microscope and dissect why, if at all, they deserve the immortality they’ve earned.

As a genre, fairy tales include every element a story needs. They exist in a time and a place, have a character who struggles, an oppositional force, an ultimate confrontation (and almost always an overcoming) of that oppositional force. In addition, their beginnings, middles, and endings can be told in a matter of minutes. Structurally, it’s incredible. But when subject to a literary analytical microscope, I take issue with them.

My two primary problems with fairy tales are their oppressively clear morals (also themes) and happy endings. Beneath the talking animals and beautiful settings lies instruction, directions, a lesson on how to live or an anti-lesson on how not to live. The moral of “The Tortoise and the Hare” is that slow and steady will win the race. “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” warns that a truth told by a liar will be considered a lie. The moral of “Goldilocks and the Three Bears”? Home intruders will be eaten.

Each of these stories and all other fairy tales exist first to instruct, then to entertain. I’ve yet to encounter a fable that has nothing to say. I’ve considered that young, impressionable minds should be instilled with values that will lead to a fruitful adulthood. I understand that fairy tales are simple introductions to complex values. I’ve also considered (begrudgingly) that “The Cat in The Hat” reads better than my manifesto on the intricacies of filial resistance to authority and the inevitable permeability and consequent arbitrariness of parental boundaries. It’s a complex topic.

As stories, though, fairy tales are monophonic. They are told by a speaker who has access to a universal truth (call it a moral or a theme) and delivers it thirty pages or so. As pedagogical devices, they work beautifully. The best stories contain multiple voices; the author is the origin, but each character can be given a voice, a narrator, the settings, the conflict. Ambiguous endings and deeply different characters are both evidence of polyphonic writing. Fairy tales invite no reader participation beyond the reader’s role as student and listener.

However, fairy tales are closed circuits by design. It’s incredibly difficult to craft a complete story with an underlying message in so few words. Eliminating the possibility for reader participation is the opportunity cost of writing a fable.

My second problem is with the phrase “happily ever after.” I don’t have a problem with its overuse. I actually appreciate its function as a mark that what preceded it was indeed a fairy tale, a fun and colorful sermon. Generally this ending can be found in princess movies, where an evil stepmother or apple peddling witch or other representation of wickedness is defeated and a princess lives happily ever after with her prince. Ideologically, I protest.

The “happily ever after” tradition destroys the good versus evil opposition and falsely suggests that good can exist forever without evil by momentarily triumphing over it. A momentary victory over evil definitely warrants celebration. Bringing eternity into it is a step over the line. Conquering evil does not vanquish it forever. Evil will return, often stronger, and entirely capable of returning the favor of conquest.

Fundamentally, happily ever after cannot exist without the presence of sadness, anger or some other form of negativity. It’s a law of the universe and princess stories violate it. To remind everyone of the formidable 50 Cent lyric: “Sunny days wouldn’t be special if it wasn’t for rain. Joy wouldn’t feel so good if it wasn’t for pain.” 50 Cent was right. Opposites are codependent and equally dependent upon the line drawn between them, establishing them as opposites.

I get that a children’s story shouldn’t be marred by suggestions that happiness is temporary and conditional, but I have an issue with canonizing impossibility. It is the strongest, most complete ending that exists. If one were to live happily ever after, the absence of struggle would slowly erase happiness into nothingness, and Rapunzel would get very existential very fast.

Though I have my issues with fairy tales, my contention is mostly playful. I think fairy tales are among the ultimate literary achievements. I have a deep respect for a story that is palatable for a child and worthy of reflection for an adult. The same story changes meaning without losing it through time. I’d love to say the same for people, but I’m afraid that we lose meaning by forgetting that at one point finding meaning didn’t matter. Oddly, that same place where meaning was a yet unformed thought is exactly where we locate it now. It’s what nostalgia feels like. Thus reveals my real reason for devoting so many words to the nature of children’s stories.

Childhood and fairy tales are inseparable. It could be that fairy tales are most believable and, for that reason, closest to reality when we’re young. Somewhere between childhood and adulthood, fairy tales seem to lose their magic, or perhaps we do. As youth retreats slowly into oblivion, the past might become as untouchable and unfathomable as the characters who were once so close to life. But I reject that.

The monophony of a fairy tale might just emerge as preferable. Though it does not invite participation from the reader, it does invite reflection. Like an unsolved riddle, it remains unchanged and steadfast in its message. It is not a matter of guessing what the story wants to tell you; it’s often abundantly clear. What’s important is a reader’s relationship with the truth a fairy tale aims to establish and in turn, the reader’s relationship with herself. In essence, it’s not about asking the story for answers. It’s about asking oneself for answers instead. Fairy tales are first a reminder to learn. Once forgotten, they remind us to remember.

As for happily ever afters, my argument only succeeds if one accepts that fairy tales happen only once in time and therefore insist that happiness is an eternal crescendo. There’s no reason to grant me this. It’s wrong.

The subject of morals in fairy tales, internal versus external beauty (“Beauty and the Beast”), honesty (“The Pied Piper”), humility and confidence (“The Tortoise and the Hare”), kindness is rewarded while selfishness is not (“Cinderella”) are recurring topics in life. Anyone who has outgrown belief in such simple plotlines could tell me that once conquered, negativity does not rest. Fairy tales, then, might be better viewed as illustrations of battles that recur.

Fairy tales have such staying power because they tell stories about the human condition. Like their subject matter, the tales themselves never lose relevance in part because they tell the ordinary extraordinarily. They sensationalize our unsensational struggles. The fairy tale repeats itself; it recurs weekly, daily, even hourly, and should be read with recurrence in mind. Each victory against doubt or anger, sadness or fear, each as momentous as it is temporary, is in itself a happily ever after.

Laura • Mar 1, 2023 at 5:44 pm

Once again, so obvious is the statement you made, yet so often not noticed. With bad comes good…repeat.

Love it