Confronting binaries in education

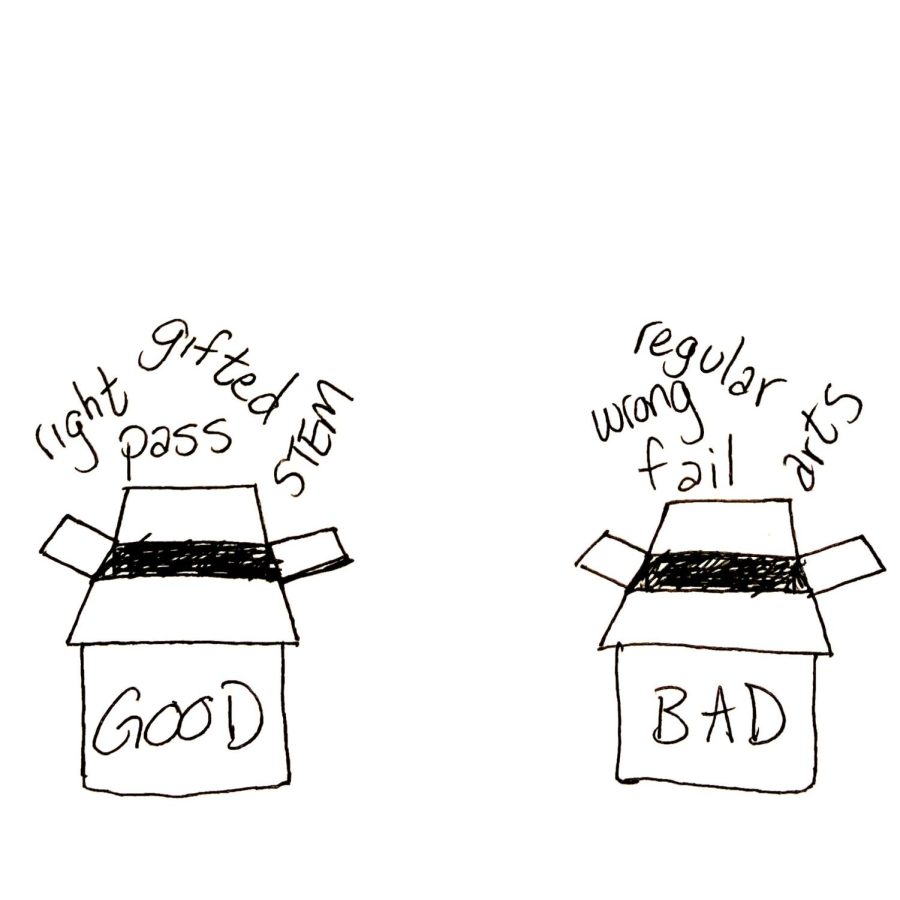

Pushing back against the urge to think in binaries is key to thinking critically. Art by the author

Apr 24, 2023

At my now defunct elementary school, there was an accelerated program called WINGS (Worthy and Important Nucleus of Gifted Students or something). They spelled longer words on spelling tests, learned long division earlier and got extremely cool erasers that no one else was allowed to have. I was not involved.

At the time, I was most upset about the erasers (especially this one that looked like Saturn that a girl named Lily taunted me with); I didn’t realize the effect that being called “gifted” or “nongifted” could have on a young mind. Looking back, binaries abound in early education and throughout American education.

This column runs through a handful of binaries, or oppositional pairs, as they exist in education. Like light and darkness or hope and dread, both sides of a binary can depend on the other for definition. In addition, Writing Center Director Megan Connor offers some insight from an educator’s standpoint. The column ends with a take on why seeing the world through binaries is both automatic and dangerous, yet capable of being challenged nonetheless.

Other than right versus wrong, possibly the earliest binary established into young minds in education is the designation between gifted or accelerated students and the others, the regular, the nongifted. When one imagines himself as either gifted or ungifted, it’ll likely give rise to another binary, feeling smart versus dumb, which can devour a young mind’s sense of confidence and belonging.

When imagining “smart students” in the classroom, one might imagine them taking notes, sitting in front of the class, asking questions. A mental link is drawn between intelligence as an assigned characteristic and the behaviors a “smart student” should exhibit. Both teachers and other students make this assumption, and often make an opposite one, that the student who doesn’t take notes, who sits toward the back of the classroom, or else stays quiet through the class period is more like a bad student, even less smart.

In either case, a set of behaviors conveniently organized as opposites leads to an assumption about a student’s academic capabilities. At John Carroll, professors of honors courses take liberties that they may not take with their “regular” section, whether in terms of pacing or adding supplemental material. At the core, however, the distinction between gifted and un-gifted students generates a fixed mindset in students who either feel themselves as helpless or as so gifted that seeking academic help equals embarrassment or failure.

On the topic of failure, one of the most damaging binaries in education is the distinction between passing and failing. In a perfect world, students would internalize the value of learning without having to worry about demonstrating mastery of the material in terms of graded tests or essays. Unfortunately, attached to every seminar, lecture, lab, elective is the implication that passing the class is more important than enjoying it.

The slogan of JCU’s Honors program is “gaudium in veritate,” which translates from Latin to “joy from truth.” It’s one thing to enjoy learning, but every student who has ever hovered between grade levels can attest that getting credit is valued over how one feels about the class. If given the option of passing miserably for credit or failing but having fun, every student I can think of (myself included) would rather trudge their way to a passing grade than enjoy a class they ultimately fail. When the choices are reduced to binaries such as pass/fail, passing a class becomes the most important thing, and retention and enjoyment recede into oblivion.

Placed within the model of pass or fail, students are encouraged to value the results of education (passing or failing) rather than the process of education. Similarly, teachers are placed in the uncomfortable and impossible position of evaluating their students, assigning numerical value to an assignment that can’t possibly fully reflect a student’s cognitive ability.

A professor’s evaluation of a student’s work almost always translates as an evaluation of the student’s character and being. The pass/fail binary, which works together with the grading system, leaves both student and instructor frustrated by the complexity of the educational process, frustrated that evaluation isn’t as easy as a rubric or a letter grade might suggest.

When asked about the problems of binary thinking in education, professor Connor began by saying that “it’s easy for professors to fall into subject binaries and talent binaries,” such as considering students as “A” students or “B” students. “That can be problematic because once you use the labels, it’s hard to see the student in any other way.”

Related to the pass/fail binary, individual assessments are graded against rubrics that feign a continuum, but generally only assess in terms of right or wrong, yet another binary. Math problems, chemical equations, or the specific names of nerve pathways in the brain have unchanging and absolute correct answers. In high school, I took a class on anatomy and physiology, where the 206 bones in the human body had definite names. I could remember most of them, though I missed and vow never to know the bones of the wrist and skull.

The absoluteness generally found in STEM is exactly why some are drawn toward those fields away from the Humanities, where one’s process and extrapolation are more centralized than a final answer. The right/wrong binary may help some brains better understand and organize truth and falsehood, meaning and folly. I admire and value brains that function in that way. Mine doesn’t.

I enjoy having the freedom to argue that Jane Eyre is about a bunch of different things. On balance, the Humanities resist the right/wrong binary, instead labeling the degree and demonstration of intentional thought as “right” and a lack as “wrong.” No course, however, escapes the pass/fail binary through which most students see it. To me, the crucial problem with binary thinking is its limitation. When one thinks in binaries, “2” becomes the largest number and “1” becomes the most important.

“In the real world, problems don’t fall neatly into binaries,” Connor mentioned. “They cross subjects and curriculums, so solving them requires analytical and creative thinking. Those who reject binaries and either/or thinking are better prepared to solve complex, realistic problems.”

I maintain that perhaps the most valuable personal trait is an ability to see one thing many ways, as opposed to seeing all things one way. Being able to try on numerous perspectives (priest, CEO, parent, someone rich, teacher, congressman, dog lover, someone retired) contributes directly to seeing things more completely, with more detail.

One of the best practices I’ve found is asking “how might a ______ see this,” inserting some of the above roles or traits (and many others) into the blank. Obviously it’s not perfect. It’s the brain’s tendency to avoid thinking like this, and it succeeds almost all of the time. To habitually challenge the automaticity is the goal. It would strengthen a student’s mind to attempt to understand how a professor might view an assignment or a grade. Similarly, the best educator strives to understand why a student or a classroom is performing the way they are.

Professors can confront binaries from their end of the educational process and actively take responsibility for the direction of a course. “It’s important for educators to engage in reflective analysis,” Connor added. “Educators should ask themselves ongoing questions about their own lessons and methods to more actively understand how their students are responding.”

If one attempts to make critical reflection the norm, one’s own mind will let them down profusely. To remember that the brain thinks this way and to momentarily resist it is a win. A symptom of a brain doing the least amount of work possible involves binary thinking, organizing absolutely everything into opposing pairs, and proceeding to label one “good” and the other “bad.”

Binary thinking happens automatically and before conscious deliberation can catch up. Moments of resistance against the automatic tendency to label and organize thoughts, people, and principles into binaries can go a long way toward understanding those things our brain would rather designate, organize, and never think about again. Everyone is more than one aspect of their identities, after all. Confronting binaries allows us to three-dimensionalize others, a process which makes us more three-dimensional people ourselves.

Bill DeBlasio • May 3, 2023 at 5:47 pm

Stimulating