What makes an excellent classroom experience?

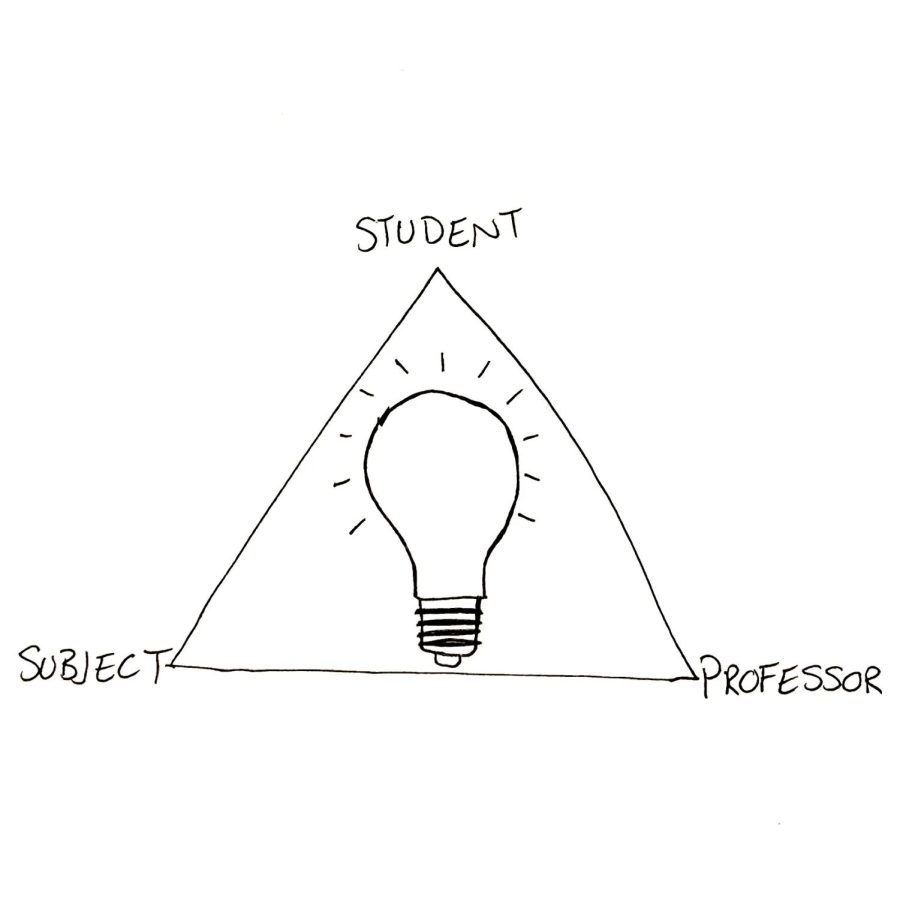

The best classroom experience is a lottery of participation and instruction. Art by the author.

May 5, 2023

Fall of my freshman year (2019), I sat in a classroom as one of many students in a classroom taught by the renowned and recently retired JCU legend, professor David LaGuardia. The class itself was a favorite of mine, and the beginning of what would be a great journey through the English major. During one October class when we were unusually quiet, LaGuardia asked whether we preferred silence. Naturally, no one said a word.

After the class, I wrote a page and a half about the classroom experience, about how a few outspoken students can inspire and encourage others who might not want to be the first to speak up. I sent it to professor LaGuardia, whose response inspired this column, three years after the fact. He recognized the value of asking what makes for an excellent classroom experience. What does it look like?

Anyone who’s been in a class with me has heard me flapping my gums, getting questions wrong and, (very) occasionally, saying something worthwhile. It takes a deliberate effort not to contribute something for me. Some students are like me and care more about voicing their thoughts than how those thoughts are received. Other students might keep quiet out of fear, a lack of preparation or (though I don’t want it to be true) apathy. Others might roll their eyes and wince every time I open my mouth.

Of course, as professor LaGuardia noted in his response, it also depends on the classroom. In some classrooms, insight and curiosity cancel hesitation and shyness, to use many of the words he used. Some classrooms are livelier than others, whether due to an eclectic group of students, fascinating subject matter (wrongful convictions, for example) or a masterfully facilitating professor. By and large, most classrooms I’ve been in follow a trend of about five regular contributors and fifteen or so listeners.

The exchange I had with professor LaGuardia was before the pandemic. On the other side of a semester and a half of online and hybrid education (i.e. cheating on tests and keeping our cameras off) I’ve noticed something different in classrooms, something I can’t with certainty call worse. The classes themselves feel less lively post-Zoom. Or maybe they’re the same as before and I’m looking back too fondly.

I’m stuck, then, at what exactly makes a great classroom experience, at what separates a robust classroom from a feeble one. Three variables that must be considered are the professor, the student, and the subject.

I might argue that the most vital element would be the professor. Front and center, a professor is faced with the choice of lecturing to the point of their own exhaustion and the exhaustion of their students’, or risking the lifeblood of the classroom on the participation of the students.

Generally, I find that the most successful professors (in Humanities courses, at least) balance their role of instructor by sharing the role of listener with their students. In other words, students appreciate a professor who listens as well as they can instruct. Professor Maryclaire Moroney of the English department comes to mind.

To place the pressure completely on the professors, however, is unfair. A professor can’t predict or control whether or not the students in any given class will hold up their end of participation. Every professor and student alike has endured those painful ten minutes following a request for “comments, questions, concerns.” It is a student’s responsibility to answer, to acknowledge at least as much as it is a professor’s responsibility to ask.

Lastly, subject matter might also influence whether students and professors come to life. Two of my more participatory classes are a linked pair on the Beatles. In terms of subject matter, I’m not sure it gets cooler than that. Some class topics are genuinely deserving of interest and consideration, or at least lend themselves more easily to care. I’ve never taken organic chemistry, but I imagine I’d like my Beatles linked pair more.

I’ll end with a word on the nature of requirement and obligation for the classes we take and classrooms we inhabit. In a sense, every class into that 120 credit-hour pile is required, but most of those classes are for core or major requirements.

Core classes get exceptionally dull, whether it’s a communications major taking their quantitative analysis requirement or a business major taking philosophy of law. In each empty chair sits the thought of “why on Satan’s glorious earth do I have to be here?” Major requirements sometimes come with that same tedium and dread (Organic chemistry is probably the best example that exists). In the English major, the 400 level seminars get very dense as well. Does the element of necessity in itself make classes unenjoyable?

I say no. Sleeping is generally an enjoyable necessity, so is eating. If one assumes that classes are necessary (or more broadly, that a degree is necessary) it would take something other than necessity to make them enjoyable or unenjoyable. Hobbies, on the other hand, are freely chosen, and the act of choosing is an important aspect of what makes choices feel enjoyable.

What makes an excellent classroom experience is a change in how we think about excellent classrooms. A room full of active students, a tactful professor, and a stimulating topic is a lottery hardly ever won. It might be better to consider your routine of going to class a choice because, for most of us, this is a sample of what the rest of our lives will look like.

If you can’t stand school, you likely won’t luck into a meaningful career. If school feels tedious, work probably will too. It feels tedious at times, perhaps most of the time, but acknowledging it is as good a first step as any. Reclamation can follow. If you think of your life as an active chain of choices and think of yourself as the operator, finding value and meaning at 10 AM on a Wednesday gets infinitesimally easier, and that’s monumental.