Routine and Freedom

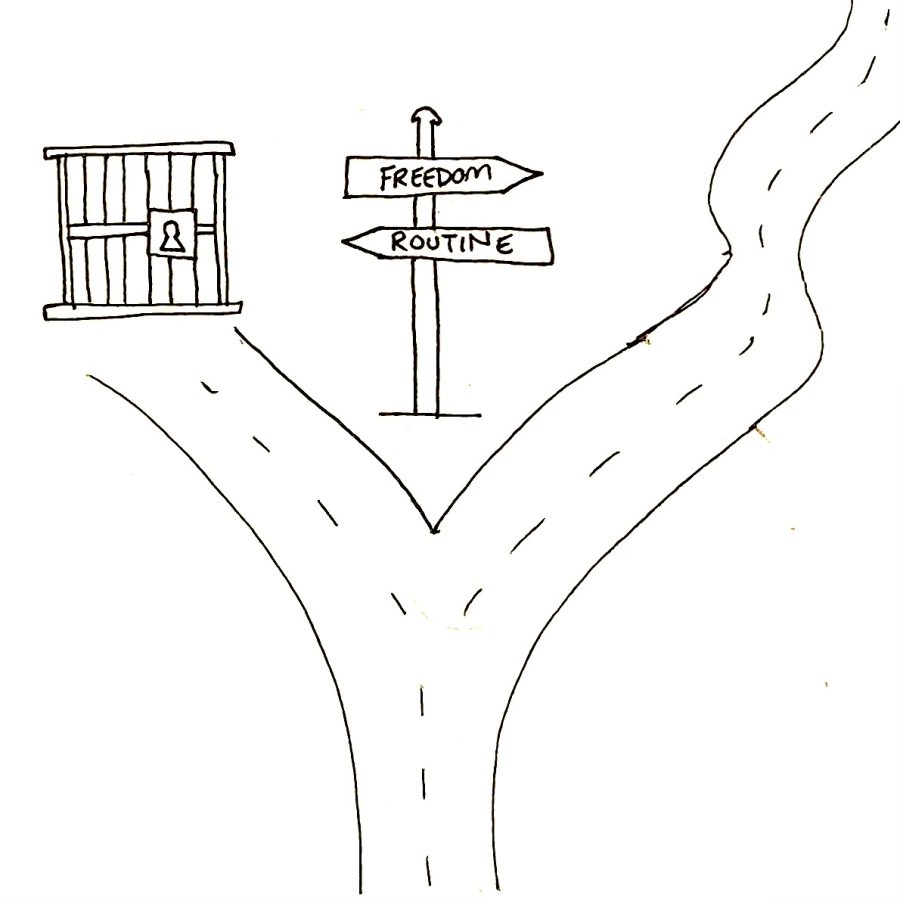

Routine may involve more freedom than initially meets the eye. Art by the author

May 18, 2023

This morning, someone woke up at 6, went for a run, got breakfast and did homework, all before clocking into their job or walking into their first class. Someone else woke up at 5:30 and someone else woke up at 5. For some people, a well-practiced morning routine marks the beginning of what could become a productive day. I admire these people.

Similarly, someone woke up at noon today and, without necessarily missing any obligations, will go from item to item on their to-do list until the day ends. Someone like this might be decompressing until three or four in the morning, setting themselves up for an identically aimless day tomorrow. I am one of these people.

This column looks at the relationship between freedom and routine. It asks and attempts to answer whether sticking to a routine robs one of the freedom or allows one to maximize it. It aims to answer the question of whether routine is a replacement for freedom or proof that freedom is being exercised and optimized.

It is a rare individual who sets an alarm for 6 or 7 in the morning and jumps out of bed smiling, ready to greet the day. It’s my contention that no one is happy about it; some people do and others don’t. I was about to write that some can do it and some cannot but I think the ability lies within everyone, unpracticed by most.

On those arbitrary mornings, followers of routines will wake up and deny the voices telling them to just go back to sleep. These people start their days in spite of those voices and I can’t overstate how admirable I find the quality.

Though not everyone has a morning routine, some have a nightly routine of journaling, writing down one good thing worth remembering, and sleeping with a diffuser or a white noise machine. Others have a nightly routine of a shower and a melatonin pill, followed by those entrancing last few minutes on TikTok or YouTube. My point is that, for better or worse, routines can be easy to find and hard to notice.

Consider a person who wakes up and works out every morning at the same time. A routine is often more complex than that but for the sake of demonstration, imagine that this person’s routine is limited to consistent waking and working out. I can imagine this person freely choosing every morning to do what they’ve determined to be good for them. I can also imagine this person trapped by the rigidity of routines, going through the motions in lieu of thinking about what the motions mean.

Routines must begin with choice. Before one decides to dedicate oneself to meditation or exercise, one must identify the importance of either, whether physical, mental or emotional, and proceed to choose how to capitalize on it. Though routines begin with the choice, they are also maintained by choice. The person who goes running every day chooses to run, though deeper ingrained routines feel less like choices.

In this way, routines are maximizations of freedom. We have the option to do what we think is best for us, and routines are freely chosen templates designed to get us there. On the other hand, loyalty to routine may also indicate a lack of choice. Simple as it may sound, spending every day doing the same things impedes one’s ability to do new things. Routines demolish spontaneity.

Revisit the person waking up and working out. No two mornings are identical; every rise and every workout will be slightly different, even without intentionality. If one purposefully aims to switch up a workout, wear different shoes, use a different hand to open the door, take a different route to the gym, listen to different music or forego music altogether, it becomes clear that the notion that routine requires identicality begins to disappear.

Take, for example, classes as a routine. On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays I go through very similar motions. Tuesdays and Thursdays are no different. Though no two classes are perfectly identical, it can become easy for one day of classes and assignments to fade into the next. I’m free to choose, however, whether I subject myself to those motions day after day. I do, as do most people.

Routines, whether they feel chosen or unchosen, can often feel like a deprivation of the freedom of choice. The monotony doesn’t have to be the be-all end-all, however. Without quitting a job or walking out of class, one can reestablish a sense of control and meaning simply by switching up a routine without abandoning it.

Even though the motions might be the same, the goal is to make the motions slightly different, to slightly disrupt the tendency toward autopilot. In his essay “Art as Technique,” Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky calls the process defamiliarization, making the familiar unfamiliar and thereby renewing a sense of initial fascination, wonder and joy. To defamiliarize something is to rediscover it and approach an understanding of it. We have both the freedom to choose routines and the freedom to keep them from becoming too familiar.

The suggestion that routine robs one of freedom fails to consider that both the construction of a routine and the regular performance of it are freely chosen. I’d even say that life is nothing but choices. Nietzsche goes as far as to identify choice as the foundational freedom, the most “advantageous advantage” in his “Notes From Underground.” Choice underlies every action, every nonaction, every acceptance, every refusal.

This evening, someone will wind down with a glass of tea or with a silent room and a journal. Someone else might try to find the bottom of their For You page. Others (like me) might routinely avoid the establishment of a routine, nonetheless following a routine. The most elemental aspect of how these nights will unfold is choice. At times choices are subtle enough to be rendered invisible, but efforts to make the familiar unfamiliar may newly illuminate what we freely choose and refuse.