Election feature: defunding the police

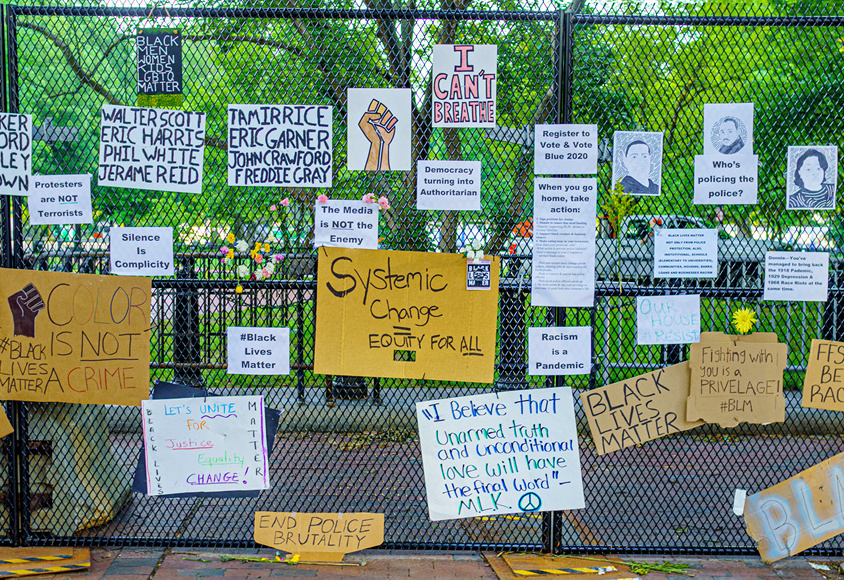

Posters hang on a D.C. fence after a June 11th rally this year.

Oct 28, 2020

This article is part of The Carroll News Elections Series, written by the students of the Fundamentals of Journalism class. For more information on these series, check out this introduction!

Protestors lie on and between the words of a yellow and orange mural on a street in Washington, D.C. It reads “Defund the Police”, and comes less than two weeks after the death of George Floyd — an African American man from Minneapolis killed during an arrest after a white police officer knelt on his neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. In the swell of a summer brimming with racial and political tensions, the protestors hold signs etched with “BLM” and wear masks as a reminder that, in tandem with their cause, a global pandemic continues to rage on.

With the election less than a month away, the Democratic and Republican candidates have addressed the debate surrounding police funding and reform in public statements. During a Sept. 16 episode of “The President and the People” on 20/20 on ABC News, President Donald Trump said it was necessary to give respect back to police officers, and every profession inevitably has “bad apples.” According to a New York Times article from July, Trump also referred to the defund the police movement as “a fad” and has criticized police for not being tougher on protesters through the summer.

Former vice president and current Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden stated in his Oct. 15 Town Hall on ABC that defunding the police is not the answer. He instead spoke in support of “community policing,” according to an ABC News article. His goal is to “arm police departments with new tools, without diminishing the police force.”

But there remains great confusion about what the phrase “defund the police” actually means and what it would look like in practice.

To defund the police would mean to take some money and resources away from city police departments and redirect it to the community in areas such as healthcare, housing and education, said Aaryn Green, Ph.D., diversity fellow at John Carroll University and the Center for Student Diversity and Inclusion. The goal of this movement is not to abolish police entirely but rather has a goal of reform within police departments and the redistribution of funding to where it can be most beneficial.

“Usually when we’re talking about defunding the police, fundamentally, we’re talking about reallocating funds to other types of societal resources like mental health, housing and after-school programs,” explained Green. “All of those things have been shown to prove that, if they are really invested in, they would help to decrease the number of crimes that we see in the first place.

Green has a background in sociology and is concerned with the role of systems in our country. One system she hopes candidates will address in the upcoming election is the police. A 2018 research report from the Urban Institute highlights the ways in which community organizations directly impact public safety, the overall health of the community and the strength of the neighborhood.

Green explained that mental health is a crucial part of the conversation about defunding and reforming the police: “[Reform] would definitely narrow the role of police in terms of them interacting and being involved in situations where they’re actually not trained to be the first responder.”

Green went on to tell the story of Tanisha Anderson, a 37-year old woman killed by Cleveland police in 2014 after they were called by her family for help during her mental health crisis. The Treatment Advocacy Center estimates that individuals with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed during police encounters. Green pointed out that police are not mental health experts, so they often enter situations with an untrained approach that for many, like Anderson, end in death.

“I would like to see candidates understand and talk about defunding the police, not in terms of simply ‘Do we pay the police more money or not?’ or [whether] police departments have more money or not, but really understanding that holistically we’re talking about restructuring how multiple systems work in our society at the same time,” said Green.

Effectively handling mental health situations and sending professionals better equipped than police officers to deal with certain situations are two major components of the “defund the police” debate.

One alternative comes in the form of a de-escalation program created by The White Bird Clinic in the Oregon cities of Eugene and Springfield called CAHOOTS or Crisis Assistance Helping Out On the Streets. The goal of the program, according to the White Bird Clinic’s website, is to reduce the number of violent police encounters by sending a crisis worker and a medic in place of police officers in instances of mental health disturbance where no crime has been committed. The CAHOOTS program in Eugene and Springfield cost about $2.1 million, as compared with the police budget of $70 million, according to Ben Brubaker, the CAHOOTS clinic coordinator.

During an NPR interview in June, Brubaker estimated that the program saves the city over $15 million by responding to 911 calls that would have been handled by the more costly police or EMS.

Much of the support for defunding and reforming the police comes from communities that have seen the broken justice system first-hand. Naudia Loftis, a 2020 graduate of John Carroll University, talked about her experiences growing up in the inner-city Kinsman area on the east side of Cleveland and her work as an advocate for her community. Loftis has been organizing rallies and championing change for Cleveland since 2017. She also works for the Tamir Rice Foundation, an organization inspired by Tamir Rice that provides after-school programs and advocates for police reform.

Loftis expressed a strong desire for police reform, especially in terms of establishing a national standard. “It needs to be at least a national standard for how long it takes to become a police officer and for any type of training you go into,” said Loftis. “I feel like that’s a pretty big position to be in —to be a police officer.”

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, “There is no universal standard for the structure, size, or governance of police departments in the United States.” A lack of national hiring standards is the reason Timothy Loehmann, the officer who killed Tamir Rice, was able to be hired by the Cleveland police department, even though he was in the firing process before putting in his resignation from his original position with the Independence police department.

When asked about where she would like to see funding redirected in the community, Loftis discussed the chronic underfunding of the Cleveland Municipal School District. “There is basically no budget for anything. Teachers are laid off. I can probably count on my hands how many textbooks we really had in elementary school, and none of them were up to date at all. By the time I got to middle school, textbooks were basically nonexistent in class,” said Loftis.

Mark Urycki, a reporter for PBS ideastream, explained the implications of the 1991 DeRolph v. State of Ohio Supreme Court Case, which argued that the state’s funding of public schools was unconstitutional. The court has ruled on this issue four different times, leaving Ohio public schools extremely underfunded with no plan on how to provide resources to students and teachers.

The Ohio Department of Education lists 100% of the students in the CMSD as economically disadvantaged. Loftis commented on the increase in budget cuts for education, especially for inner city schools. “I feel like [budget cuts are] a huge problem because it’s taking away from the kids that have to go to those schools. [Not everybody] gets the luxury of going to a private school,” she said.