Why you should jaywalk

The dreaded Belvoir/Silsby/Wrenford intersection.

There is a cartoon I think about a lot when I walk (I promise this isn’t another “walking column”…okay…maybe just a little). It reimagines a city block –– pedestrians lining the sidewalks, a woman walking her dog, shimmering storefront windows –– except that the roads are replaced with thousand foot crevices and the crosswalks with pirate-ship-like planks.

Sure, the metaphor is a bit on the nose, but I think the point the cartoon is getting at is valuable: roads are endless networks of space dangerous to human beings.

I’ve encountered this viscerally in the neighborhood around John Carroll.

Take, for instance, the hellscape that is the Belvoir/Silsby/Wrenford intersection. A block north of Campion Hall, I frequently cross this intersection on walks. If I am heading south from Pervis Park down Wrenford Road, to continue on the same street I need to cross lanes of traffic three times while watching out for cars from six possible directions.

When the intersection is busy, it is often impossible to decipher when it is my “turn” to cross, so I usually just wait for a brief lull, say a Hail Mary, walk on into the street and keep my head on a swivel, poised to athletically dodge any oncoming motorists I may have missed.

The worst part of this, for the quality of my walk, is that it breaks the flow. If I’m deep into a song or a podcast, I have to pause it to focus on not getting flattened by the omnidirectional threat of wheeled death machines. If I’m having an interesting thought, I invariably have lost my place by the time I re-emerge from the other side of the asphalt no man’s land. And, if I’m walking with a friend, our conversation lulls as we stop to coordinate our simultaneous crossing. Roads break my stride, if you will.

Not only do roads kill creativity, they destroy community and they inspire individualism. For instance, to walk to my neighbor’s house, which is probably about 100 feet directly across the street, I have to spend a solid three minutes walking down the street to enter the crosswalk and then back down the street to their house. Instead of simply taking 15 seconds to just walk across the street, I have to waste my time using this narrow, government-approved strip of pavement –– the only place where I may legally cross the street. Talk about government overreach.

And for what? So some antisocial freak can zoom his tinted-window Subaru down the street at 80 miles per hour any time he pleases?

And if you think I’m being pedantic here, if you think I’m making mountains out of molehills, if you think that no one actually enforces jaywalking laws, let me tell you about my freshman year living in Campion Hall. Anyone who lived there that year will surely recall the brief period when University Heights Police Department decided that they’d play Road Secret Police.

As you know, Campion and Hamlin halls sit just adjacent to the rest of campus, separated by Belvoir Road. So, to get to campus, you have to cross a stop-light controlled intersection.

For about a month, a black UHPD squad car would intermittently sit by the crosswalk stopping students who “illegally” crossed the street and ticketing them. A friend on my floor got slammed with a $100+ ticket for crossing a street.

Today, cars own the streets not people, and there is an entire legal regime in place to make sure it stays that way.

And the worst part is that it wasn’t always like this. Prior to the ubiquity of the automobile, city streets were a gathering space. Kids played in the streets, adults talked and traded with each other, communities formed.

But, as cars began flying down city streets in the early 20th century, pedestrian-involved accidents increased at alarming rates. The first impulse of cities was, sensibly, to crack down on the cars. In 1923, Cincinnati, for instance, attempted to require that all cars in the city be equipped with a mechanical governor limiting their speed to 25 miles per hour.

Unsurprisingly, this spooked the nascent automobile industry. They successfully lobbied against Cincinnati’s proposed speed limit, and then they embarked on a national campaign to shame “jaywalkers.” They took out ads mocking jaywalks, held events promoting “street safety” and, most importantly, lobbied to criminalize crossing the street incorrectly. In doing so, they pulled off history’s largest, if slowest, heist. They manipulated the public consciousness, turning roads from a place for people into a place for cars: They stole the streets.

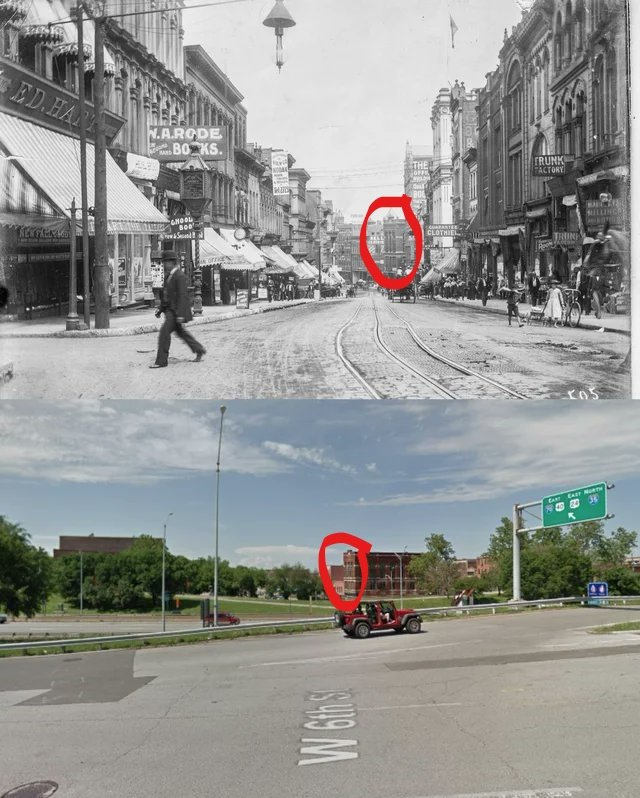

The scars from the crime are still visible in cities to this day. Across the country, bustling early 20th century neighborhoods, with shops and apartments and restaurants and bars, were leveled for the construction of highways.

Heartbreaking side-by-sides (like the one below) show the extent of the wounds –– and I don’t use heartbreaking likely. When I look at pictures like this, I see the decades of communities that never were, of neighbors that never were, of friendships that never were. All that culture and community, sacrificed to the industrial spirit of Ford Motor Company.

And sure, there was some transitory benefit in all this. The ease of automobile transportation and the suburban boom cars kicked off surely drove a large amount of economic activity. But I wonder what that boom would have looked like driven instead by a massive investment in public transportation? Would it not have been of comparable size?

Most of all, though, I wonder what this country would be like if we didn’t carve up our communities with asphalt and concrete.

I wonder if we’d be less individualistic, walking or taking the train instead of hiding behind tinted windows, interacting with fellow drivers only to honk or flip each other off. I wonder if we would be less antisocial, conversing not on the acrid online public squares of Twitter and Facebook but instead in physical public spaces just beyond our front door. I wonder if we’d love our communities more, travelling together and not alone.

Most of this car-free vision is probably just a utopia existing only in my naive, young, college-student mind. But if our communities looked just one-tenth more like that utopia than this world, I think we’d be much better off.

But it is not too late to start building utopia. For most of human civilization, roads were occupied by people; the automobilization of roads is a relatively recent development. And, if COVID showed us anything about roads, it is that the car’s ownership over them is fragile. As restaurants struggled with new limited capacities, cities began allowing establishments to set up shop in the streets or in parking lots –– a glorious repurposing of that ugly pavement. My home city of Chicago even closed down a busy downtown section of Clark Street to make room for outdoor dining.

Even more radically, a campaign in Berlin to create a massive car-free zone –– a zone larger than the entire city of Chicago –– has gained traction recently. These developments make clear that cars own the streets only so long as we allow them to.

So pedestrians: Cross the street however you please, play a game of street hockey, throw an impromptu block party, barbeque in the middle of the street. They can’t stop us all.

Walkers of the world unite, we have nothing to lose but our crosswalks!