Giba’s Claim: Output before input

The pursuit of a life dedicated to creation over consumption.

Defining fear

I’ve not been feeling a proclivity for coherent long form writing recently, partly because of fear and a host of other struggles. Peaks and troughs on the graph of life are just reality.

Lately, returning to my notebook and sketchbook in shorter bursts has become my primary way of sifting through the muck in my mind.

On a page, I can name things, poke them with my pen, find what’s bothering me better than any other way I know.

Writers are always told to “write what you know” — to go toward the fear and write what scares you. Fear pops up nearly every time I write, and that’s half the reason I feel so compelled to return to the page. The other side is that I love telling stories and truly believe in their power.

Investigating the fear is usually how I track down what really matters to me, what I really want to say in my work. This isn’t very easy.

Fear is just behind the work

Discussing fear is not always visibly present in a writer’s production; usually it’s behind nuance and a little less on the nose. From the outside, a lot of the work we see from creatives is marketed to us to maximize the appreciation of the work in isolation — the struggle and the doubt and the fear are undeniable aspects of the creation of anything, but we don’t always see that. The life of the artist then seems appealing to us if we don’t acknowledge the reality of the dark side of creation.

There’s a dangerous problem with romanticizing this dark side of creation too — the stereotype of the “tormented artist” that creates beautiful art and burns out into oblivion: 27 Club members, Vincent Van Gogh, David Foster Wallace, Jean-Michael Basquiat, Sylvia Plath, Ludwig van Beethoven, Mac Miller.

There’s some form of fear within every creator. Steven Pressfield, the author of The War of Art, identifies this feeling as “resistance.” It has many names. What’s clear to me is that facing this internal force is essential to my personal harmony.

So naturally, today I’ll be writing a bit directly about fear and a way I’ve been working to engage it daily.

Dueling fear

One fear I often have is neglecting creation, forgoing a day without any dedication to creation and instead being absorbed into a day of consumption.

If you’re like me or anyone else with access to the Internet, we have infinite semantic saturation at our fingertips that constantly give us paths toward distraction unless we implement systems in our lives to block the paths.

On the contrary, I want to maintain that I value consumption and understand that inspiration to create is nourished by input — but just like anything, too much can create problems. Imagine a growing tree: we’re the trunk and the leaves, but what do our roots need in order for us to grow? External stimulation — water, nutrients, sunlight. The roots are our inspiration. Without roots embedded in art we admire, we can be led to artistic stagnation. Too much consumption will cause some roots to rot and others to wither however, hurting the overall health of our tree.

Recognizing this, my tenet is creation over consumption. I want to give more than I take.

This is a lifelong commitment; I’m taking it one day at a time.

Tom Sachs’ rules

Last year, I came across Tom Sachs, a contemporary artist based in New York City. He has a series on YouTube of short industrial essay films (directed by Van Neistat) that have helped me define why and how I work artistically.

Tom is one of my roots. His philosophies and rules that guide the work in his studio have changed how I look at the world. Here’s one of his rules from a video, a simple conviction:

Output before input.

A rule to live by — to do forever.

Practice

It’s clear enough: when I wake, an act of creation has to come from me first before I input or consume anything. Five minutes spent pulling something unfiltered out of myself.

The mystic aspect of this practice is that at some point in our rest, our waking minds and subconscious meet for a subconscious séance. In those immediate waking moments, I still feel tethered to the unconscious (check another of my columns about dreaming here).

I’d say I remember my dreams around 80% of the time I sleep, and the more I practice outputting first thing in the morning, the more I’m able to recall my dreams that previously would slip away in the day. I’m really fascinated by dreams, so remembering them is really important to me despite their content.

In sleep, my pillowed head is trying to make sense of whatever irrationalities of reality I experienced in my waking hours. I like to think of this as my brain organizing itself, similar to what happens after I sort through notes from class and put them where they need to go.

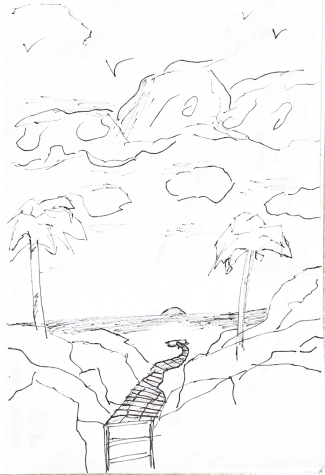

Having spent some time practicing, I find that for around five minutes or so, there’s this ethereal gate that sticks around, and I can walk around that particular dream’s pasture: smell it, touch it, hear it, hang with the horses and such.

A sunrise in the mind

Usually in those waking moments (although not always), every detail is right there, waiting to be tugged out and imperfectly transferred into the material realm.

I often crack up at the absurdities I recall — discussing dreams with my roommates on our morning walk to class has become one of my favorite things this semester. Of course, it’s fun to toss around ideas for what the dreams might mean, but in the end all we’ve got is guesses (which is enough).

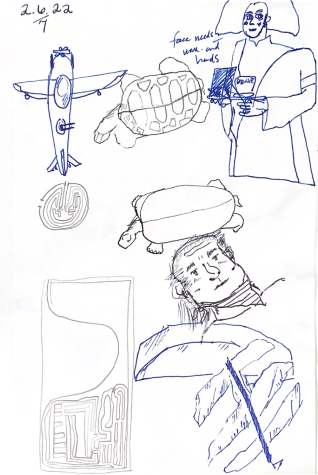

Sometimes my dreams are utter nonsense, but usually I can grasp something — a short, vivid description, a conversation, a distinct image.

Reveries

I find company taking the waking moments sheltered in my notebook. It feels like I’m meeting with an old friend.

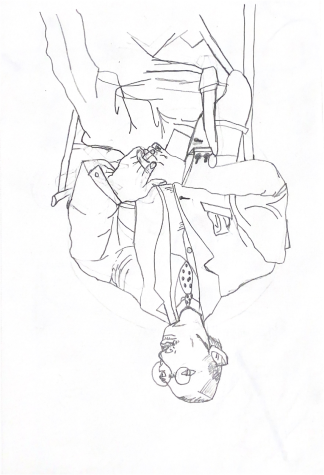

Instead of writing, what’s come to me most naturally in recent output is drawing. I like to practice and study drawing, but this simple act of capturing something from recent dreaming allows me to play.

In order for my illustrations to improve overall, I’m keeping the 50% rule in mind: 1/2 drawing time is play, 1/2 is study. Just five minutes of play with a groggy mind is an intentional way to start my day.

One scene from a dream came back to me shortly after I got on the subway once:

A giving ritual

With enough repetitions and an intentionally constructed environment to support morning output, eventually this decision doesn’t need to be made anymore — it’ll become a habit, a simple ritual to which my mind gratefully and gently wakes up to.

Instead of consuming something in the world, I get to start by giving outwardly.

This is basically the simplest way I can face my fear of meandering through a day without output. Each time I show up, that fear will become that much more disarmed.

The fear itself I’m not so sure goes away — I remember that Kurt Vonnegut said that it gets even harder as you get older. What I’m doing right now is just getting to know that fear better. Awareness is the key.

With enough time, I’ll have a constant output of little writings, thoughts, unfiltered diagrams and docketed dreams.

In these purer moments, it’s a time when I’m metaphorically naked — uninfluenced by the day’s ways. This journey is a companion to a favorite quote of mine from Steve Jobs, one I invite you all to reflect on in closing:

“Because almost everything — all external expectations, all pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure — these things just fall away in the face of death, leaving only what is truly important. Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose. You are already naked. There is no reason not to follow your heart.”

Create today. Just play.

Jack Giba is a Senior from Pittsburgh and is the Opinion Editor of The Carroll News. He can be reached at jgiba22@jcu.edu.