The evolution of the doomed romance

Sep 29, 2022

Since the beginning of time, audiences have been attracted to doomed romance. “Orpheus and Eurydice” and “Romeo and Juliet” are some that come to mind as the catalyst for the prominence of this subgenre; they set a precedent for pieces of art that would follow them.

With a myriad of books, television series, plays and movies showing a couple that is “meant to be” that have to cave to internal and external circumstances that cause their love to falter, there are plenty of options for the general viewer.

Cinema has done justice to this category since film was created. Films such as “Casablanca” and “Roman Holiday” were early entries into the genre and “Atonement,” “Brokeback Mountain,” “Call Me by Your Name” and “La La Land” have kept the genre going strong in recent years.

With the creation of so many great doomed romance films, some entries are bound to get lost in the pool of media. Listed below are three underrated films that belong to this genre along with why you should take the time to not watch them but EXPERIENCE them.

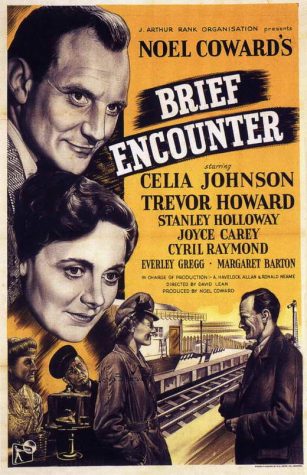

1.) Brief Encounter (1945)

“I do love you, so very much. I love you with all my heart and soul.”

“I want to die. If only I could die…”

“If you’d die, you would forget me. I want to be remembered.”

Where should I begin with this one? An adaptation of Noel Coward’s play of the same name, director David Lean tells the story of British wife Laura who falls in love with Doctor Alec Harvey after they have a “brief encounter” during her weekly shopping trip. After they continually run into each other by coincidence every Thursday, they begin to develop a deep love that they both know can’t go anywhere, as they are both married. Because of this intense love, Alec decides to take a job offer in Africa in attempts to end his love of Laura once and for all.

The story may seem simple on the surface, but the nuances in Coward’s script and Lean’s direction combined with great performances by Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard, make it one of the best films of the 20th century.

The use of narration is sometimes scoffed at for being a “lazy” way to tell a story but hearing Laura’s thoughts as she recounts the tale of her love affair with Alec is the epitome of the capabilities of cinema.

The black and white cinematography, coupled with a central location of a train station, make for a smoky haze that emphasizes the yearning of the leads. A great example of this occurs when their final moments together are interrupted by a friend of Laura’s. Lean darkens the background of Laura as the voice of the friend is slowly being overpowered by the blaring of a train horn. As darkness engulfs Laura, the camera slowly enters the most well earned dutch angle in cinematic history. Then, jump cut to a train chugging out of the station before cutting back to Laura, who is now standing beside the train after almost committing suicide.

The tension that is at the heart of this scene works so well because every beat leading up to this moment shows how palpable the love Laura has for Alec is. In terms of doomed romances, “Brief Encounter” set the standard in many ways as to what an earned romance should look like.

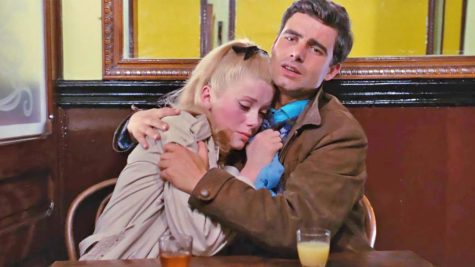

2.) The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1967)

“Why is Guy growing so distant? I would have died for him. So why aren’t I dead?”

While this may seem like a deep cut for some, this Jacques Demy 1967 musical drama starring icon Catherine Deneuve and Nino Castelnuovo is quintessential French New Wave viewing. This may be considered a less casual watch since the film is not only in French, but it is also completely sung through with no spoken dialogue.

The film follows young lovers Geneviève and Guy who are separated due to Guy’s mandatory service in the French army. After he leaves, Geneviève learns that she is pregnant, much to the dismay of her overbearing mother. When Geneviève and her mother accidentally fall into a friendship with a rich jeweler named Roland Cassard, she is pressured by her mother to forget Guy and marry Roland.

The second half of the film follows Guy after he comes back home from war to learn that Geneviève is married. He suffers a rough period before marrying the nurse who took care of his sickly aunt who dies while he is in the army.

The film then jumps ahead a few years and we see the first interaction between Guy and Geneviève since their prior tearful goodbye at the train station. This scene is so heartbreaking to watch because the audience was able to see how in love these two characters were before the circumstances of their situation forced them apart.

As Geneviève gets in her car and leaves with their daughter, the music swells and Guy is joined by his wife and son as the credits begin to roll. This is known as a perfect ending.

This and the overall story are made that much better by the use of color throughout the film as well. “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” is full of light pastels that are used to create love through a color palette.When things turn sour, the pastels then contrast the negative emotions that the two leads feel towards each other.

If one can get past the idea of a French musical with no spoken lines of dialogue and just let the film completely wash over them, they might find themselves watching their new favorite movie.

3.) Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019)

“You dreamt of me?”

“No. I thought of you.”

Sticking with French films, our final movie is widely considered to be one of the best films of its year. Written and directed by Céline Sciamma, the film follows the painter Marianne who is commissioned to do a wedding portrait for Héloïse. The portrait was originally supposed to be of Héloïse’s sister, but she committed suicide to avoid the marriage which caused Héloïse to be taken out of the convent as her replacement.

Marianne has to paint Héloïse from memory as she will not sit for the actual portrait because she is against the marriage. Once Héloïse’s mother leaves the house, Marianne and Héloïse fall into a whirlwind romance that they both know can only last for a few days.

I am not over exaggerating when I say that this movie is flawless. The scarcity of dialogue makes every sentence uttered impactful and the deliberate use of diegetic music heightens the passion the two leads feel for each other.

The film’s small cast and centralized setting create a feeling of both isolation and vastness that help the audience become entranced by the story and characters. Coupled with the allusion to the Orpheus and Eurydice myth, these elements unite to intensify every scene.

The continued references to this myth are my favorite part of the movie. When our main characters have a discussion about the meaning of the ending, it is used to foreshadow the last time Marianne and Héloïse see each other. The main theme of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth is the idea of Marianne’s gaze on Héloïse for her portrait.

The film ends with Marianne staring at Héloïse during the symphony after they haven’t seen each other in years. “Summer,” a composition from Antonio Vivaldi’s masterpiece “Four Seasons,” is being played by the orchestra and Marianne watches as the love of her life slowly begins to cry; this song is one that they played within their short time together. Her tears slowly evolve into a bittersweet smile which signals to both the viewer and Marianne that Héloïse still cherishes their love.

Hopefully this peaks the interest of whoever reads this to watch one of the aforementioned films and gives you a little more appreciation for the doomed romance genre. Even if there is a film that I didn’t mention, these movies are a great way to get in touch with the hopeless romantic inside all of us and let out a good cry.