An analysis of my two favorite endings

Opinion Editor, Eric Fogle, discusses his favorite endings in media and their significance.

Oct 10, 2022

Perhaps the only thing more important than an ending is a beginning. Unlike paintings, experienced all at once, works of art involving music or language begin and end in time; they travel through time. Artists choose a beginning and an end. This column considers how two different artists chose to end two respective works of this temporal kind of art.

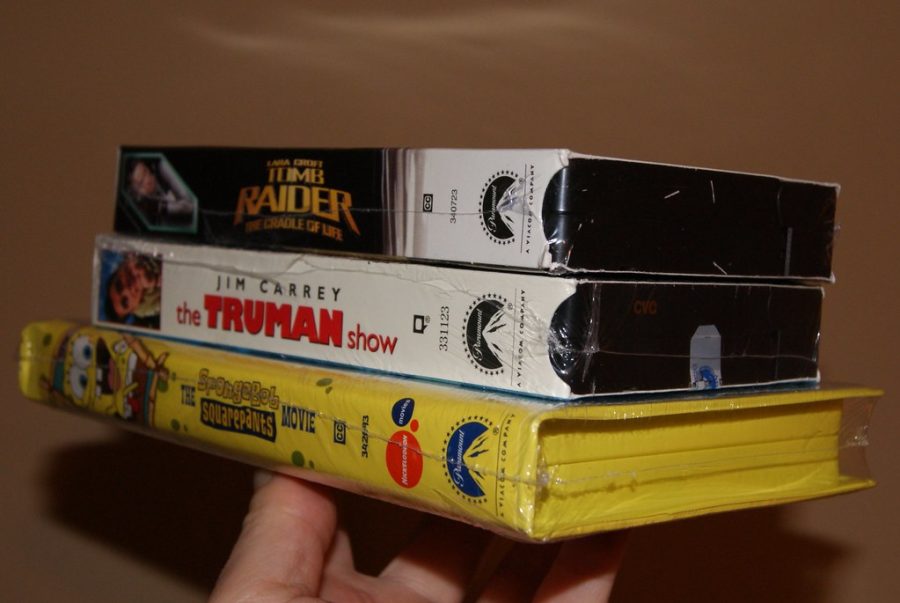

Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men,” published in 1937 and Peter Weir’s “The Truman Show,” released in 1998, stand apart from other pieces of fiction while sharing similar–and rhetorically brilliant–endings.

I’ll include a spoiler alert here in case those reading this didn’t read Steinbeck in high school and/or, for some reason, haven’t given themselves the gift of watching “The Truman Show.” I must recommend reading “Of Mice and Men” and watching “The Truman Show” as both works reveal truths about what it means to be alive and reveal those truths masterfully.

“Of Mice and Men” follows two friends, George and Lenny, through California as they try to find work as ranchers during the Depression. Near the end, George shoots the intellectually disabled Lenny, to whom he has acted as a friend, brother-figure and guardian. George commiserates with Slim, a friend he made on the ranch where most of the novel takes place. Curley (a main antagonist) and Carlson (a secondary antagonist), share the moments after the incident with George and Slim. George’s pain overwhelms him. Slim, along with the reader, can only guess at the conflict raging in George’s mind. Steinbeck, however, gives the last line to Carlson, a very minor character who ends the book with this line: “Now what the hell ya suppose is eatin’ them two guys.”

“The Truman Show” ends with Truman, the movie’s main character, taking a bow and exiting the stage he thought was his life. He chooses to walk through a door which promises him nothing other than to recede into the empty promise of life behind him, a world constructed around him but not for him. The ending asserts the power of agency, namely the dormant strength we have to change our lives and the courage it takes to move on. The movie could have ended there. The last seconds are instead given to audience members who watched The Truman Show and cheered for Truman’s exit. The last lines are spoken by two security guards or police officers who ask what else is on, entirely oblivious to the act of life and living that flickered on their screen moments before. Writing about it gives me chills. Watching it stuns me.

In both of these works, the ending follows the resolution. In a real way, the endings aren’t necessary, and that’s part of what makes them so good. They’re not necessary to the plot, but they’re necessary to the point. “Of Mice and Men” could’ve ended with an image of George ravaged by guilt and responsibility and it still would’ve been canonical. If “The Truman Show” had ended with Truman exiting into the blackness of the open door, it still would have delivered a haunting message. Both endings went above and beyond in similar ways, offering the reader/viewer a different idea on which to reflect, to entertain, to fear.

A reader or viewer, by the end of the book, may have completely missed the significance of these endings. By giving these characters the final lines, Steinbeck and Weir reinforce the takeaways of their respective works by putting oblivious, undeveloped characters on display. In this way, their last lines function as a question: “did you get it?” or, perhaps more fittingly, “did you miss it?”

This kind of ending could be called the anti-lesson. In my piece on fairy tales, I condemn the condescending pedagogy of a “moral,” a lesson the character learned that is clearly meant more for the reader than any character. Rather than to deliver the lesson in a hackneyed and instructive way, these two works end with an anti-lesson centering on a character who clearly didn’t get it.

An anti-lesson shows both confidence in the writer and faith in the reader. At best, it’s bold to devote the last line, the last opportunity to impact the reader or viewer, to an anti-lesson. At worst, it’s foolish. However, if a writer makes their point clearly in the resolution, they can afford to end a piece without restating everything the piece should have been able to say on its own.

Therein lies the beauty of the anti-lesson: it shows what the piece is not meant to do or be or what a reader is not meant to take away. When executed effectively, the anti-lesson says more than any lesson can. Here, the absence of direction more effectively directs; the absence of instruction also instructs. By leaving us with an example of what not to do with the work, the author/director can turn us in the right direction.

Establishing an undesirable outcome can motivate an audience to take steps to avoid that outcome and instead approach something more constructive. Consider anti-smoking commercials that use testimonies from smokers who have a stoma in their throat resulting from oropharyngeal cancer. A viewer doesn’t need to know what “oropharyngeal” means to be frightened by the idea of having a hole in their throat.

To put it simply, the anti-lesson is a warning. Perhaps because it is under-utilized, I believe a warning can instruct much better than an instruction. An anti-lesson says “This is what will happen if you don’t get the point. Miss the point and you’ll be unchanged, unchangeable, unmoved, unmovable forever. Miss the point and you risk being exactly how you were before and one moment closer to being exactly that way forever.”

But I suppose none of this really means anything.