Dread is your ticket of admission

To contemplate one’s existence might be the best use of one’s existence. Art by the author

Apr 15, 2023

Companion piece to a column on hope, available here.

In November 2020, I took a five hour drive with my friend Grady to Slate Run, PA. There, we walked in the woods, stared at the night sky, and demolished Cheerios while taking the time to write down our thoughts. We drove back the next morning. All told, we were there for under 24 hours. During that time, however, I was fascinated by the idea of what, if anything, can anchor us to reality. At one crucial point later in the night, I wrote “existential dread” on a loose piece of paper and put it in my wallet. It’s been there ever since.

Grady and I have a history of aphorisms. A personal favorite is “The sky is blue behind the clouds,” a short reminder that when sadness or stress overwhelms us, it’s easy to forget that sadness is a state that comes and goes like storm clouds. Sometimes it rains, but a return to stability means a return to clear skies, to an unobstructed heavenward gaze.

Though I can’t recall what exactly was weighing me down in the fall of 2020 (besides everything else wrong in 2020), I remember trying very hard to convince myself that whatever it was didn’t matter at that moment. I was mistaken and it surely did, but I was missing something. My woes (whatever they were) surely mattered, and my effort to prove to myself that they didn’t turned out to be evidence that they did. I would not have tried so desperately to ignore or forget something I deemed inconsequential.

We move through life from youth to adulthood, from schools to jobs to marriage to middle age to old age effortfully yet inevitably. It’s almost never easy, but the time passes and we get used to it, though life will still surprise us. Through it all, the weight of existence is bearable yet undeniable. A succinct explanation still eludes me.

At the time I tried to explain my thoughts to Grady. To demonstrate, I used the only thing on hand: a pencil. I attempted to explain that at any given moment any given human carries the burden of existence on their shoulders simply by existing, and that it might as well weigh as much as a piece of paper. My proof was that he and I stood across from each other in spite of the individual battles we’ve won, lost, weathered nonetheless.

At that moment, I began to wonder whether difficulty is not an obstacle to being but a precursor to it, a necessary condition. Holding a pencil in my hand, I imbued it with every breakup, every unloved love, every shed tear, every moment of embarrassment, every death of a loved one, every robust fear. Yet still, I held it at arms length between us. Every obstacle we meet, whether we lose to it or overcome it, is thrown onto the burden of memories we inexorably bear.

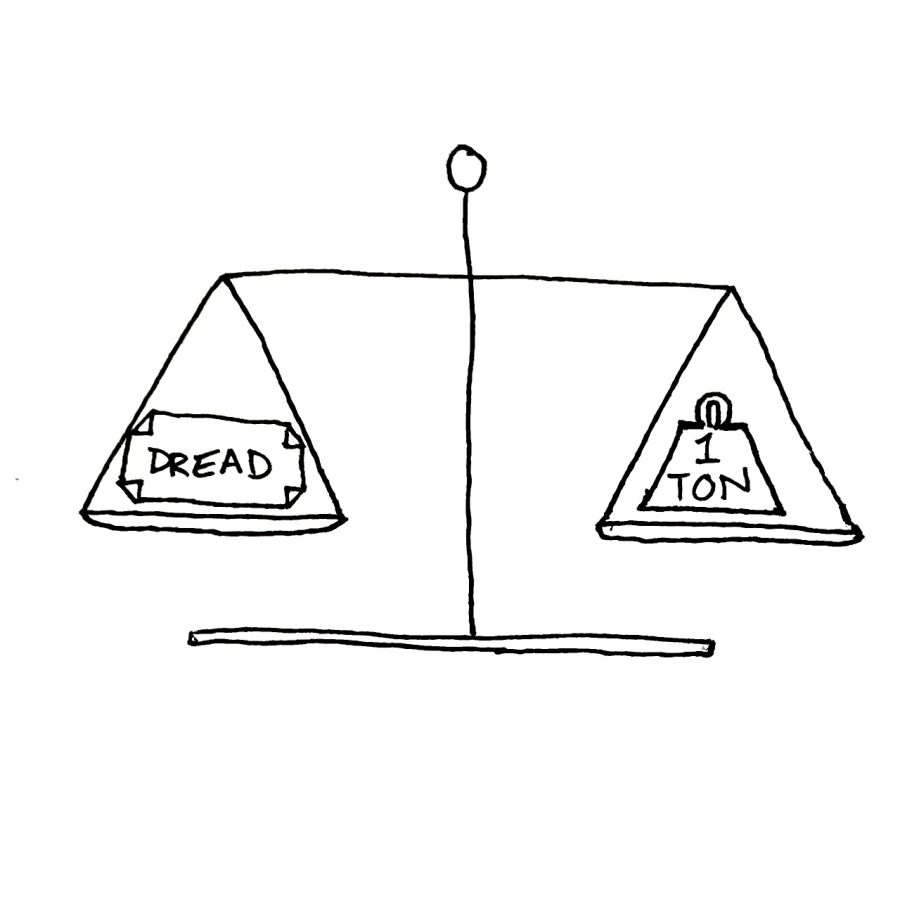

Afraid I wasn’t making my point well enough, I found a piece of paper and wrote “existential dread” on it, picking it up to prove to myself how simple it was to carry. The weight of the world, “it weighs about as much as a piece of paper,” I remember saying to Grady. It was a rallying cry, an insistence that each day is a ferocious and triumphant walk farther into the unknown. Wondering if one is living life correctly is evidence that one is; it’s the ticket stub.

Since then, the list of obstacles have only grown for Grady and I alike. Living in New York City, Grady encounters a set of challenges completely different from mine in suburban Ohio. Carrying that existential dread in our pockets, we persist.

To me, dread is the natural and occasionally unbearable byproduct of existing. Being bogged down by the questions of whether you’re good enough, whether you’re living correctly, whether life is wasted because you can imagine a life where you’ve made more of yourself, are to me symptoms of existence. Absence of these doubts is evidence of a half-lived life, a short, forgettable and forgotten existence.

Often there is a redundant urge to avoid these thoughts. I call it redundant because if the thought to escape thoughts is among one’s thoughts, one’s thoughts are worthy of being thought. In other words, if you’re thinking about thinking, you’re thinking about the right things.

Why, then, call it a ticket or admission?

Often I wish to avoid the idea that I may not be living as well as I could be. I can imagine a life lived perfectly, an existence performed without a single mistake. Reality, of course, can’t bring this production to life, but to bear the disconnect between projection and reality in mind proves worthwhile. To be discouraged by internal whispers of a life you haven’t lived and to live imperfectly despite that discouragement is one of the more admirable traits of living. I refuse to call it a quality I have; it is a quality of life, a reward to be claimed with minutes of reflection, an irredeemable prize that comes with the ticket of admission.

Dread is evidence of contemplation. Dread follows only from the worthwhile speculation and questioning of the many meanings of life. Someone who doubts, questions, wonders at the value of life most clearly understands life’s value. Someone who understands that he will never understand what he wishes to know goes a much longer distance than someone who thinks he’s found all that is worth looking for, and calls off the search for meaning in the undying meantime. If you’re thinking about these things, even if they overwhelm you at times, you’re doing it right.

Since Slate Run in 2020, I have done my best to remember that dread neither traps nor liberates us. Of course, contemplating the value of dread has not eliminated stress from attacking me from new and surprising angles. Though its form continues to change, dread remains a present variable, a question waiting to be answered, a challenge waiting to be met. There are days when looking dread in the eye is the last thing that I want to do, and those days turn into yesterdays soon enough, members of the collection.

There are days when I’ve done the best I can with dread. On those days I’ve walked, read, wrote, thought, drove, laughed, cried, loved, asked, answered. Other days I avoid such direct confrontation with dread. Those are often my least memorable days. That growing mountain of days, some great, some terrible, most forgettable, all lived through, are stacked onto that “existential dread” slip currently folded up in my wallet. And taking the sum of all of them into consideration, it still weighs about as much as a piece of paper.