“All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost.”

– JRR Tolkien

If the average person is familiar with the works of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, they are most likely aware of the “Lord of the Rings” films and perhaps the less successful “Hobbit” trilogy. They probably know that these stories originated in the forms of books, but there lies the extent of common knowledge. The fact of the matter is that these stories, as magnificent as they are, only begin to scratch the surface of what Tolkien accomplished in his eighty-one years of life. He not only told richer and grander stories than (arguably) any other writer in history, but practically defined the term “world-building” and mastered the art in a way that has not even been challenged in the fifty years since his passing.

Since this is a Keim Time column, I will begin by briefly accounting my history with John Ronald. I, like many middle-schoolers, became enamored with the films based on his work. I remember enjoying “An Unexpected Journey,” the admittedly charming first movie in the over-elongated “Hobbit” trilogy, but what really stuck with me was “The Lord of the Rings.” Between watching the films and playing the LEGO video game adaptation, I was fascinated by how cool the story was. An everyday short guy is entrusted with the most powerful object in the world and must embark on an epic journey of a lifetime? What’s not to love?

Though my appreciation of the films remained, my passion definitely waned as I went through my high school career. I remembered the epic scale, but never stopped to consider anything more deeply. That all changed once I journeyed to John Carroll University.

This particular installment of Keim Time is dedicated to Kate and Elizabeth Ferenchak: the women who brought me back into the world of Tolkien, taking me deeper down his rabbit hole than I had ever thought possible. After becoming friends with these two lovely lasses, I was quickly introduced to their near-obsession with the author. They forced me to watch the “Lord of the Rings” films again, but this time, there was so, so much more.

From the Ferenchak twins, I learned about “The Silmarillion” and the many other stories that take place in Middle-earth and the larger world of Arda. I hardly retained any information they dumped onto me, but I was intrigued. I was so intrigued that I made it my mission to become fully engrossed in Tolkien’s Legendarium. All these months later, would I say I have become engrossed? No. That would be an absurd understatement.

Last spring, I was treated to the voice of Andy Serkis reading the entirety of “The Hobbit,” a charming but simple introduction to the world of Tolkien. The next natural step was to read the entirety of “The Lord of the Rings” in a little over a month. The 1030 pages breezed by as I became deeply emotionally invested in the struggles of the Fellowship of the Ring. Would Frodo make it to Mount Doom? Would Aragorn be able to defend Helm’s Deep? I already knew the answers, but I had to keep reading. I couldn’t stop. Practically every free moment I had during that time was dedicated to that book. It was the most addictive book I have ever read.

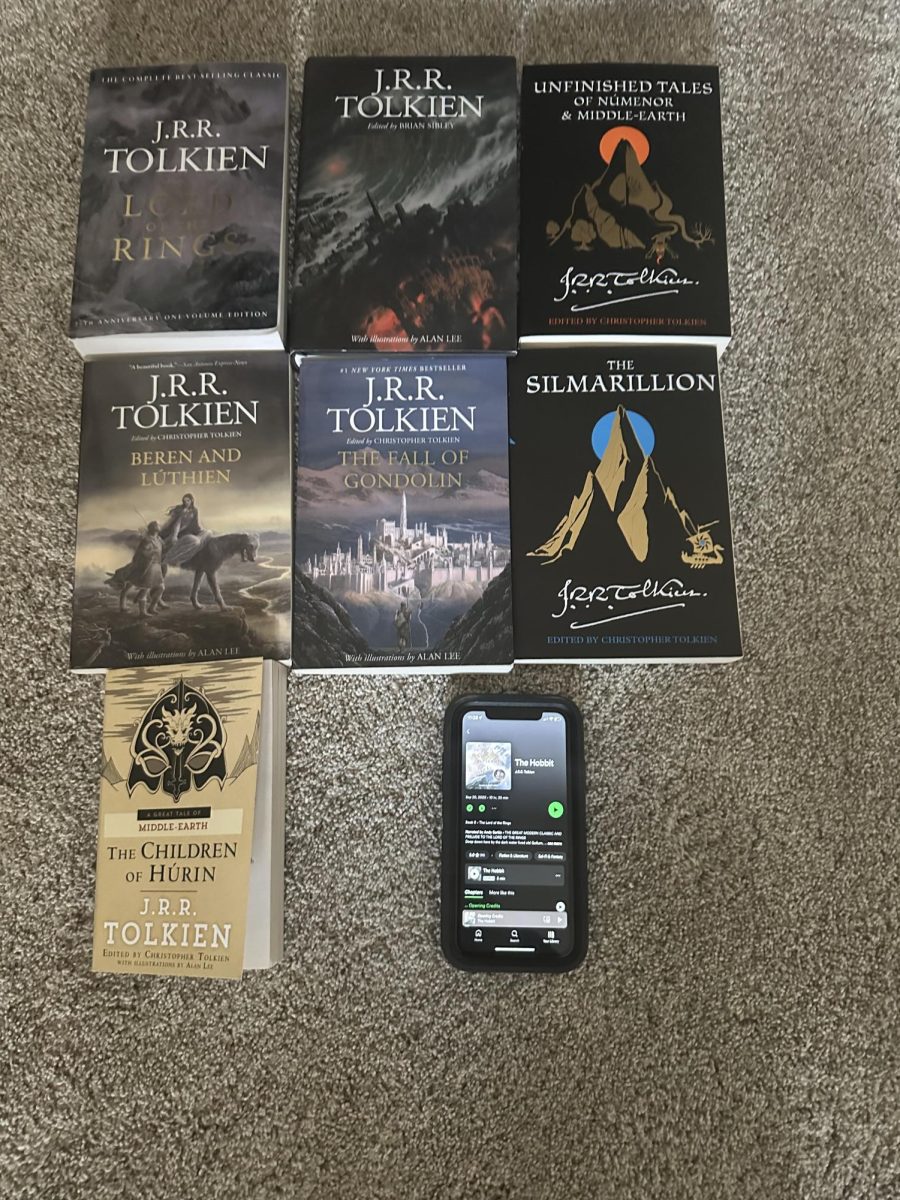

Once I was finished with that adventure, I was incredibly satisfied. But I wasn’t finished. From there, I read “Beren and Lúthien,” “The Silmarillion,” “The Fall of Gondolin,” “The Children of Húrin,” “The Fall of Númenor” and lastly “The Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth.” I couldn’t get enough. Every chapter I read, every piece of lore I learned, every new character I mourned pulled me deeper into this world. In some areas, I overshadowed Kate and Elizabeth, the people who brought me there in the first place. I couldn’t speak Elvish as well as Elizabeth, but I knew who Queen Ancalimë was, dang it!

Now that I am decently well-versed with the realm of Arda, I can safely say that Tolkien’s worldbuilding is the greatest I have ever seen and no other creator even comes close. John Ronald worked on his stories for nearly his entire life, from his childhood until the day he died, and that effort is blatantly evident in his works. Practically every character mentioned in any given story has a backstory, a family tree, distinct motivations for why they do the things they do.

JRR did not do anything halfway. He had the history of Middle-earth chronicled, to the year, for a period of over 5,000 years. If he was writing a story that didn’t comply with existing lore, he would continue to work on it until it aligned with everything that had been previously established. If a character in a book alludes to some distant folk tale, you can be sure that tale is told in its entirety in one of his works.

All of this in-depth lore is tied together by a spectacular series of stories. Of course, “The Lord of the Rings” is the most well-known, and for good reason, but “Beren and Lúthien” is well worth the time of any fans of fantasy looking for a beautiful love story. “The Hobbit” is close to LotR in the realm of notoriety and functions well as a small-scale whimsical fantasy romp. “The Children of Húrin” is a book that can really stand on its own with little or no prior knowledge of Tolkien’s lore. It may, however, come with severe emotional damage as character after character is killed by the forces of evil, or just unfortunate circumstances. The other books I mentioned earlier are strong as well, but definitely work best when seen as companions to his other works. The endless array of similarly-named Elves who appear in “The Silmarillion” can be confusing for even the most seasoned of loremasters.

John Ronald is nothing short of a master of writing and I could write about his works non-stop. His stories touch on themes such as the effects of war, the corruption of power, respect of the natural world, the treatment of women in society and so much more. However, if I started writing about those themes, I would have enough content to fill the Red Book of Westmarch.

For now, I will simply encourage readers to give Tolkien’s work a shot. He could surprise you with how enthralling his tales can be. If you like one story, try another. Then another. Then another. After all, the road goes ever on and on.