Why you should pay attention to your dreams: the power of unconscious healing

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Mar 11, 2021

In January, while I was on a silent retreat, I had a dream where I died. Everything was burning while I was in a mall. I hid behind a pillar as riot gear-clad executioners cleared the room of survivors. Protestors smashed windows at one of the entrances of the mall to my left while the sentries ambled perilously toward me. I remember accepting my fate, laying down with my feet poking out from behind the pillar, closing my eyes and exhaling a final breath as they approached. Then I woke up.

Sounds like a nightmare, right?

I remember this because I wrote it all down immediately after waking. I sat there in the dark, with my pen and journal, wondering what I could make of it all.

Despite the peaceful silence of the retreat, COVID-19 was still in full swing, Trump’s impeachment trial was happening, the Capitol had been stormed the week prior and I’d been experiencing more emotional turmoil than ever before. I’d later learn that much of the contents of dreams come from emotional concerns. Evidently, my own emotional concerns took the form of a death dream.

Reflecting on the retreat, I repeatedly returned to the dreams. I had questions, so I brought them up to my therapist and started researching.

I read a nonfiction essay from 2017 by Cormac McCarthy titled “The Kekulé Problem.” McCarthy unpacks the question of language, its origins and how it relates to our unconscious, framing his ideas around the revelatory dream of the chemist August Kekulé.

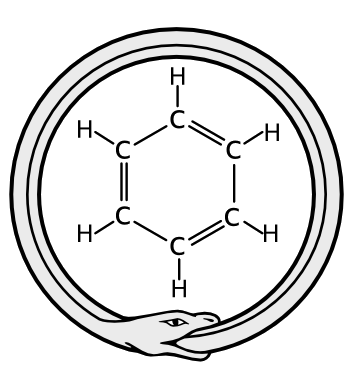

Sometime during the winter of 1862, Kekulé had a dream that revealed the structure of the benzene molecule. When he dozed off, his unconscious showed him the ouroboros, a snake eating its own tail, which is an ancient symbol of death, rebirth and the cycle of life. He woke declaring, “It’s a ring. The molecule is in the form of a ring.” And, long story short, it was.

“Why the snake?” writes McCarthy, a novelist and playwright, in his essay. “That is, why is the unconscious so loath to speak to us? Why the images, metaphors, pictures? Why the dreams, for that matter?”

For McCarthy, the answer lies in the origins of language. Language, McCarthy says, is only around 100,000 years old compared to the roughly 2 million years the unconscious has been formed in human minds.

His own Kekulé-esque epiphany came one morning when he was taking out the trash. McCarthy figured simply that the unconscious is “just not used to giving verbal instructions and is not happy doing so. Habits of 2 million years duration are hard to break. … The log of knowledge or information contained in the brain of the average citizen is enormous. But the form in which it resides is largely unknown.”

So, we’re shown inexplicable images and dreams, which is just an ancient way that the unconscious mind communicates with us. It’s trying to tell us something; it’s asking us to pay attention.

McCarthy, reassuringly, believes the unconscious is covertly looking out for us: “The unconscious wants to give guidance to your life in general. … The unconscious intends that [dreams] be difficult to unravel because it wants us to think about them. To remember them.”

I certainly remembered them.

Spurred by McCarthy’s essay and wanting further answers grounded in recent neuroscience, I returned to the book called “Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams” by Matthew Walker, a scientist and professor of neuroscience and psychology at the University of California, Berkeley.

From Walker’s book, I was reacquainted with Sigmund Freud’s disgraced status as a result of his early theories on dreams being disregarded by modern psychology and neuroscience due to their scientific unreliability. Today’s neuroscience practically tears his theories on dreams apart.

In ancient times, the Egyptians and the Greeks believed dreams came from divinations, from the gods. It wasn’t until Aristotle dismissed these claims and grounded dreams within an individual’s recent waking moments that other ideas of where dreams come from began to surface.

Near the end of the 19th century, however, Freud played a major role. He reasserted Aristotle’s theory that dreams came from within the brain. That seems trivial now, but neuroscience was in its infancy during Freud’s time, and a claim like this could neither be confirmed nor denied by science at the time. In the present day, neuroscience has revealed to us so much more about what actually happens in our heads.

Recently, Walker conducted a number of experiments to explore some of his own theories he had about dreams.

One of his theories is that the dream state of REM (rapid eye movement, our deepest and most rejuvenating phase of sleep) “takes the painful sting out of difficult, even traumatic, emotional episodes you have experienced during the day, offering emotional resolution when you awake the next morning.” Basically, he hypothesized that the dream state acts as a sort of built-in therapist for tackling emotionally charged memories. The release of adrenaline is completely shut off when we enter the dreaming REM state. It’s “the only time during the 24-hour period when your brain is completely devoid of this anxiety-triggering molecule,” writes Walker.

The experiment he conducted to test the theory affirmed his hypothesis: “It was the dreaming state of REM sleep — and specific patterns of electrical activity that reflected the drop in stress-related brain chemistry during the dream state — that determined the success of overnight therapy from one individual to the next. … It was not, therefore, time per se that healed all wounds, but instead it was time spent in dream sleep that was providing emotional convalescence.”

His finding was further affirmed by Rosalind Cartwright at Rush University in Chicago, who studied the dreams of people who were showing signs of depression as a consequence of difficult emotional experiences.

“Right around the time of the emotional trauma, she started collecting their nightly dream reports and sifted through them, hunting for clear signs of the same emotional themes emerging in their dream lives relative to their waking lives,” Walker explains.

Cartwright performed follow-up assessments a year later to determine whether the patients’ depression and anxiety caused by the emotional trauma had resolved or persisted.

“Cartwright demonstrated that it was only those patients who were expressly dreaming about the painful experiences … who went on to gain clinical resolution from their despair, mentally recovering a year later as clinically determined by having no identifiable depression,” Walker writes. “Those who were dreaming, but not dreaming of the painful experience itself, could not get past the event, still being dragged down by a strong undercurrent of depression that remained.

“It was only that content-specific form of dreaming that was able to accomplish clinical remission and offer emotional closure in these patients, allowing them to move forward into a new emotional future and not be enslaved by a traumatic past,” Walker concludes.

In what has been a traumatic year for many of us, the power of dreams and sleep can help us overcome the wounds and darkness experienced in our country and our world — a darkness that has sucked many of us into a void of drifting, disillusionment and broken promises.

Whatever nightmares or fear you may experience when you sleep, rest assured that there is a reason for it all, no matter how absurd. Be open to what the unconscious shows you — it wants to help; it wants to communicate. My hope is that you listen to your dreams and find peace in the land of the unconscious.