“Hadestown” takes the Cleveland Playhouse to the underworld

Drew Steinbrink writes about the experience of going to “Hadestown” with John Carroll.

Mar 17, 2023

“Hadestown,” Anaïs Mitchell’s 2006 musical, came to Palace Theater in Playhouse square this past February. Although the show premiered in 2006, it did not reach Broadway until 2019. When it did, it was a massive success. “Hadestown” won eight Tony awards and was nominated for 14 during the same year. When the Kulas Grant for Fine Arts provided tickets to about 20 JCU students, they were snatched up immediately, and for good reason.

The show is based on the Ancient Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. Orpheus, the son of a muse, is a gifted musician and Eurydice is his lover. Hades, who has grown jealous of their relationship, continues to drag Persephone back to the Underworld earlier each year, causing the winters to lengthen and worsen.

Eurydice is rundown from trying to cope with this disaster and the Fates, who (as Hermes notes) are always just over her shoulder, tell her there is a way out: go to Hadestown and sign her life away to the god of the Underworld. They remind her that it is enough of a struggle to take care of herself, let alone Orpheus. After Orpheus, wrapped up in his songwriting, repeatedly misses her calling his name, Eurydice agrees. In one of the best moments of the show, the Fates turn to the audience and tell them not to judge her; as not even she is heroic when the chips are down, – we would not be either. The show follows Orpheus as he goes down to the Underworld to retrieve her.

Mitchell reimagines the classic Greek myth in “Hadestown.” While no setting is named, the music is in an undeniably American style and it takes place roughly around the Great Depression. Hades is reimagined as an aristocrat industrializing Hadestown, as they call the Underworld, and the lights flare every time he appears. This, contrasted to softer, more natural lighting when Persephone is onstage, makes him feel all the more intimidating. The lighting has the same effect as the song “Why We Build the Wall,” when Hades proudly describes his exploitation of the people of Hadestown. He is a fantastic villain because of how unabashedly he does everything, and criticizing industry is a running theme of the show. Not to give too many spoilers, but Orpheus encourages the residents of Hadestown to unionize. The theme is cleverly worked in through design choices such as the clothes the residents of Hadestown wear.

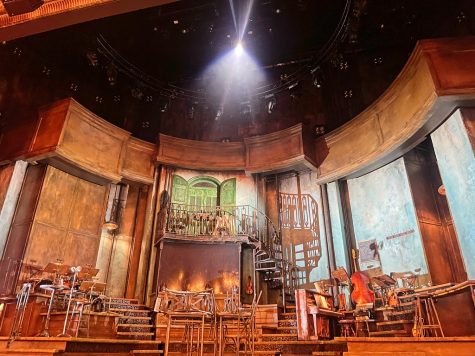

The show has been referred to as a folk opera and the genre of the music varies quite a bit throughout the show. There is a small jazz band who sits directly on the stage and whom Persephone introduces by name. The jazz style comes through on songs like “The Road to Hell” and “Our Lady of the Underground,” whereas “Wedding Song,” is more of a country pop sound and “Why We Build the Wall” has the classic call-and-response of work music. The band shows versatility in their style, shifting genres effortlessly. “It grew on me, the characters really came to shine through the musical pieces. The small band was very impressive with their adaptability,” said Mario Esquivel ‘26.

The set is nearly identical to that of the Broadway production. The musicians sat in a semicircle around the stage, creating a closed-in feeling. That closed-in feeling created a sense of intimacy between the characters in the Overworld and a sense of being trapped in the Underworld. When the setting shifts to the Underworld, the set expands to form dark, red-lit alleys which only makes the setting more ominous. Although the set is small, Hermes’ narration paints a vivid picture of what is happening off stage.

Hadestown is a fantastic musical in its own right and perfect for those who grew up reading Greek myths. It seamlessly blends a Greek story with an American setting. Seeing it in a theater is something that cannot be replicated listening to the soundtrack.